![]()

![]()

|

May 1997 No. 21

OUR INDICTMENT I don't intend here to make a critique of Molinari's book, although I may perhaps do that at some other time or place. I only wish to take the opportunity to state what is, it seems to me, the true sin, the very great sin of John XXIII, which is the following: to be pleasing to everyone, he did not always make known, nor always sufficiently defend, the truth and the discipline of the Church. Of those authors who, to my knowledge, have recently applied themselves to pointing out some of the stains on Pope John's "halo," none have gone so far as to utter such a grave accusation. This is why the duty that I undertake is new and of a very ticklish nature. I confront it with great anxiety, the more so because it seems to me almost to be committing an act of ingratitude towards a dear person who held me in esteem (cf. Roncalli, A. Letters to the Bishops of Bergamo, Bergamo, 1973, p.133). Convinced nevertheless that the truth, outweighs every other consideration, I wish to express my thoughts very clearly, even if by doing so I should appear to be presumptuous, irreverent or shocking. There were many who exploited the goodness and the kindness of Pope Roncalli during his lifetime. As he himself loved history, knowing that it was cruel and pitiless, he will pardon me for this indictment, born of the grief caused by the chaotic condition of the present-day Church, a condition for which, it seems to me, he also was responsible. A cardinal said after his death that it would take 50 years to repair the damage done during his pontificate. The statement was diplomatically denied, but, uttered or not, I believe that it expresses a good bit of truth. That which follows, naturally, is solely a matter of the reflections and the personal judgments of the author; judgments, moreover, not influenced by the recent publications, for the good reason that they were implicitly expressed, even if only in private, from the time that the campaign for the canonization of the "good pope" was begun. Indeed, when I was urged to sign the petition in favor of this cause, I refused, thereby stirring up the disapproval of the promoters. The criterion which forced me to make such a disagreeable refusal was precisely that one which is diametrically opposed to the fundamental norm of our great man's actions; a norm recently recalled by the Postulator himself in Osservatore Romano of July 4 [1975]:

...and weak I might add! Well, against this basic mode of behavior, practiced not only as a private person but even while occupying posts of supreme responsibility, I brutally oppose the practice and the norm of St. Paul: "If I were still trying to please men, I should not be a servant of Christ" (Gal 1:10). One cannot set up "peace at any price" as a rule of government. Since I have taken upon myself the thankless task of devil's advocate, I am going to try to proceed...in a scientific manner by recalling the classical, and apparently paradoxical thesis according to which "the virtues, carried to their perfection, are necessarily connected in such a way that if just one is lacking, none are perfected, and one cannot therefore speak of sanctity." My venerated teacher, Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, under whose direction I wrote my doctoral thesis precisely on this theme of the connection of the virtues, was insistent on the point that, in processes for canonization, one had to examine in depth to determine if the virtues had attained in the subject their degree of perfection, their vital cohesion, their cooperative force, because if only one of them is not perfect, none of them will be. Consequently, if a man possesses the greatest charity but lacks moral courage, or the virtue of fortitude or of prudence, he will be a good man, an excellent Christian, but certainly not a saint in the full meaning of the term. In a lecture given to candidates for holy orders on December 12, 1945 (and which, I believe, remains unpublished to this day), the celebrated theologian developed his thought in the following way:

Listen to St. Thomas on this subject:

Was that good-naturedness, so highly praised in Roncalli, always supported, accompanied and corrected by all the other virtues, especially by true prudence and true fortitude? There, is the real basic theological problem in judging the sanctity of Pope John. Wishing at any cost to be benevolent, sympathetic and agreeable, did he not perhaps establish a method of government which has weakened the discipline of the Church, as a consequence of which, along with many other causes, we now find ourselves immersed in a frightful ideological, moral, liturgical and social chaos? The reply, as far as I am concerned, is positive and the accusation is thus very grave: it is on me therefore that the burden of proof is incumbent. It is not a matter here of revealing enormous or secret deficiencies in the way in which he directed the Church, but simply of recounting a few symptomatic acts which express a certain style of government; a style which, emanating from such an elevated seat, was then fatally spread, by concentric circles, throughout the entire Catholic universe.

SYMBOLIC EPISODES Here are a few of those symbolic episodes, significant of a style, of a method, of a system, concerning which I'm not sure that his most extreme panegyrists have given sufficient thought. Let us begin with an episode which in itself is rather modest, but which sets forth very nicely the personality of the protagonist. On February 12, 1962, the well known Apostolic Constitution Veterum sapientia was published. It contained in its norms one stern law, that is, the chair will be taken from professors of theology who, over a period of time, will not submit to giving their teaching in Latin. A German bishop, accustomed, as a good German, to always taking things very seriously, hurried to Rome, troubled and distressed, to lay before Pope John his grave problem:

The Pope sent him away with a big smile accompanied by some benevolent words:

The one who told me of this event is now dead, but he was a person worthy of being believed and very well informed on Roman affairs. The episode will seem to be of little importance, but, in my eyes, it is revealing of a mentality and of a manner of acting which has little coherence and little firmness. The following act is however of public knowledge and constitutes a far more grave indication of weakness in the government of the Church. The Dutch episcopacy, wishing to prepare its people at the Council well in advance, issued a joint letter, which was quickly translated into several other languages. In it was suggested, and moreover in sufficiently clear terms, the principle that the validity of the decisions of the coming Council would be dependent upon their reception or rejection by the faithful. Rome quickly detected the implied but very certain democratization which would flow from these positions, and the letter was withdrawn from circulation, by order of higher authority. Card. Alfrink, the Primate of Holland, immediately descended upon Pope John XXIII to point out to him what dishonor such a disciplinary measure would cast upon the episcopacy of an entire nation: Pope John, in order not to displease the Dutch, annulled the measure, thereby inaugurating that series of capitulations which would culminate later, under his successor, in the non-condemnation of the notorious Dutch Catechism. Given the fundamental norm of his private and public life, which was to never give offense to anyone, the Pope was, obviously, radically allergic to condemnations, and especially to solemn and formal condemnations. In this, he was certainly not faithful to the teachings of his master, Msgr. Radini-Tedeschi, Bishop of Bergamo, who, in one of his first pastoral letters, formulated his essential duty in these words:

A COMPROMISING PAGE OF "HAGIOGRAPHY" It will be useful to pause here a moment to more fully enlighten ourselves, with the aid of Roncalli's own words in his biography of Msgr. Radini-Tedeschi (3rd ed. Rome, 1963), on the saintly and energetic style of this bishop whom the future Pope saw as the image of the good shepherd: The personal keynote of his nature was integrity: an integrity beyond any debate and surpassing any praise; an absolute love of that which is Good. From that came his fearlessness, his ardor in battle, his attraction to danger, one could say, as well as his powerful activity. One saw, sometimes, in his speech and in his writings, both public and private, great vehemence of language, some strong and scornful expressions,...but the Grace of the Lord had ennobled these natural gifts of man and rendered them more fruitful and worthy of veneration in the priest and the bishop (p.l06). Strong and vigorous government above all; this was the true reflection of his character and of his personal temperament:

This citation should not be seen as an irrelevant matter, since it puts the finger on how the young Roncalli, under the teaching of his bishop, had some very clear ideas on the inviolable duty of joining mildness with strength and, in case of necessity, giving primacy to the latter. However, I believe that no honest panegyrist could apply to Roncalli the words that he wrote concerning Bishop Radini-Tedeschi.

OTHER ACTS OF WEAKNESS Here is an example of his weakness. From the time that he was nuncio at Paris, he made no secret of his cordial detestation for the radically evolutionary doctrines of the famous Jesuit, Teilhard de Chardin. But, elected Pope and solicited on all sides to put de Chardin's works on the Index - they were an abundant source (among others) of the encroaching doctrinal confusion of today - he slipped away, limiting himself to approving the Monitum of the Holy Office of 30 June, 1962, (which was grave in its content but ineffective in practice) and uttering the historic phrase:

Jesus, St. Paul, St. John the Evangelist and numerous great and holy Popes did not limit themselves to blessing - an easy and sympathetic task - but also exercised the solemn duty of condemning and anathematizing. "The whip was not made for the hand of Roncalli" says Molinari (op. cit. p.149); however Jesus himself used the whip. And thus it came about that an Ecumenical Council was summoned, which, for the first time in the history of the Church, did not dare to openly condemn the greatest error of its day, atheistic Communism. History and the future centuries will certainly never pardon Vatican II for failing to stigmatize, in a most peremptory and draconian manner, that atheistic Communism, or Marxism, which constitutes the most powerful enemy of Christianity in the 20th century. Even the name itself never appeared in the authentic text of the Council! (Whoever wishes to know the maneuvers by which, against the wishes of numerous bishops, they succeeded in not even mentioning atheistic communism in the Acts of the Council should read The Rhine Flows Into the Tiber, by Fr. Ralph Wiltgen, TAN Books, 1985). Some will say: but when Gaudium et Spes was voted, Pope John XXIII was already dead. Very true: but it was he who in the opening discourse announced, with the greatest solemnity and the greatest clarity, that he wished, in avoiding condemnations, to make use of the medicine of mercy rather than that of severity, under the specious pretext that it was better to expose the truth than to condemn the error, the more so since it would be a matter of errors that had already been condemned. Thus he ignored the laws of human psychology according to which a formal condemnation, renewed under the threat of practical sanctions relative thereto, is far more efficacious than a brilliant theoretical dissertation. Pope John and Vatican II at that time set an example in such a way that, today, the hierarchy, at all levels, no longer has the healthy courage to put outside of the Church those who openly deny the most sacrosanct dogmas. The Küng case demonstrates this. The Dutchwoman Cornelia De Vogel, who converted to Catholicism in 1943, recounts (in her book Lettres aux Catholiques de Hollande et ŕ Tous) how she appealed to Card. Alfrink to reprimand those Catholics who were denying dogmas. Here is his response, which would henceforth become typical:

The origin of this non-usage, brought into the Church for the first time, is found in the behavior of Pope John XXIII. Under his reign, one began to consider the problem of condemnation no longer by paying attention to the common good and to the meaning of a book in its obvious and objective terms, but rather to the personality and the intentions of the author, whose "sacred" individual rights, according to the new ecclesiastical ethics, take precedence over those of the aggregate of the faithful. But let's come back more directly to Pope John. Shortly before the encyclical Pacem in terris, there appeared in Osservatore Romano the famous "Fixed Positions" which stigmatized any collaboration whatever with movements ideologically founded on erroneous doctrines, for the obvious preventative reason that such a collaboration, by a sort of osmosis, would lead, with the passage of time, to absorbing the doctrines on which they are based.

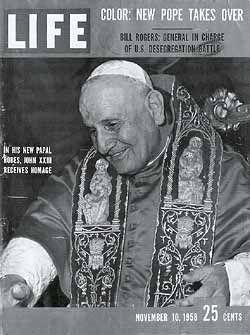

Pope John XXIII performing the "obedience"

ceremony

But this classical and ineluctable law, always put forth by the preceding popes and especially by Pius XII, reaffirmed again under the eyes of John XXIII, would be radically contradicted in his encyclical Pacem in terris (#55). Here are the precise liberalizing affirmations:

It is true that in the immediate context, the conditions for such encounters are afterwards spelled out, but the conditions are partially contradictory and always blindly utopian, as the history of the collusion between Catholic movements and Marxist movements of these past 10 years has abundantly demonstrated (and of which one will see more and more in the future). The cited text is fundamental for the Johannine turn-about and represents a veritable revolution in the practice of the Church; a revolution whose very grave and deleterious consequences will weigh heavily on the future of civilization and of the world. We have here the ideological basis for the "historic compromise," not only for Italy, but for the entire world. What Giovanni Spadolini writes in his interesting book Le Tibre Plus Large (Milan, 1970), seems incorrect to me, when he affirms that, in Pacem in terris, one finds "nothing new in regard to the preceding Pontificates." On the contrary, #55 represents a radical reversal of direction when it legalizes collaboration by Catholics with movements born of anti-Christian ideologies - a collaboration up until then positively forbidden for the simple reason that "he who goes with a lame man learns how to limp" (a fact we see verified every day). There is no need to be a specialist in Marxism to perceive how many subtle infiltrations of this ideology have henceforth penetrated into the thought and action of different groupings of so-called Catholics. To please whom were the "Fixed Positions" approved? And to please whom was the revolutionary #55 of Pacem in terris signed? In taking as a rule of government to never displease anyone, one falls fatally into doctrinal contradictions and practical confusions.

TURNED TOWARDS THE COMMUNISTS AND….. THE SUPERIORS There now comes an episode relative to the much discussed audience granted to Khrushchev's journalist son-in-law Adjubei; probably to please him (not to mention other contingent and more decisive reasons): in any event, it was foreseeable that the audience would be utilized in favor of Communism. Early one morning in May of 1963, I found myself on the piers of the port of Civitavecchia, awaiting the arrival of the boat from Sardinia which was bringing some people for an audience with the Pope…While chatting with some longshoremen of the port, who of course were Communists, I heard them enthusiastically praising the Pope for having received Adjubei. They were interpreting the gesture as a symbolic act of tacit approbation for the Communist movement, and all my attempts to dispel such an interpretation were to no avail. Probably inspired by one of their leaders, they replied:

That the behavior of Pope Roncalli may have at the same time weakened the restraints put on the advance of Communism in Italy, he himself has rendered account of, if it be true that on the night the results of the elections of 1963 were released, he burst out in sorrow, exclaiming: "This, I did not wish! I did not want this!" But the policy of "being pleasing" can lead to such results, and to many other disastrous consequences. To "be pleasing" or to avoid displeasing someone can, in addition, be a source of the dissimulation of the truth or, at the very least, occasion of the lack of courage to express it. Here is another little personal instance. In July of 1950, I was invited to lunch by the Nuncio Roncalli in Paris. For three hours at a stretch, he beguiled me with a most amiable and interesting conversation which left me greatly enthused; an enthusiasm which later was partially mitigated when I realized that he was saying more or less the same things to everyone. On this occasion, the Nuncio had some harsh words for the French Dominicans who had, in one of their publications, sharply criticized the affected and bookish Latin (a Latin neither classic nor Christian) with which the Biblical Institute had translated the Psalter, by order of Pius XII:

I allowed myself to say, weakly, that they had done well, since, in questions of philology, the pleasure or displeasure of the pope is of no account. But the Nuncio himself basically thought as the Dominicans did; so much so that, once elected Pope, he gave the order to resume use of the former Psalter, correcting it only in its less auspicious passages or where it corresponded poorly to the He- brew text. Here is the testimony on this subject of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre in his book A Bishop Speaks (Angelus Press, p.115):

But if he had been less tactful, he would have been obliged to say it earlier to Pius XII himself. By all indications, it seems to me that his obedience to his superiors was too passive. Thus, most certainly, by not contradicting them, even when it had been his duty to do so, he was able to enjoy that "precious" interior and exterior peace which limits one, in large measure, to a life without turmoil. Putting aside the fact that at the time of his formation and his employment "lack of moral courage was a plague in the Church," as A. Fogazzaro saw it, exaggerating a bit, in his book The Saint (Milan 1906, p.243), there are some accusations which sharply point out the tendency towards an excessive submission. Everyone is the offspring of his calling, and every calling inevitably entails a professional deformation, the more serious in proportion as the subject is the more malleable. During almost all his life, the future pope Roncalli was a subordinate: secretary, delegate, nuncio. Molinari writes, not very tactfully, that:

He had been too obedient all his life to learn later, in his old age, how to command; for it is not at all true that he who has known how to obey knows how to command. In reality, it is a case of two operations psychologically and morally structured in opposite ways. (And unfortunately John XXIII obeyed his iniquitous private secretary Msgr. Capovilla). In addition, in a letter from Istanbul to professor Donizetti, in March of 1938, the future pope wrote the following:

The irony of history! A man who, throughout his whole long life was always too submissive, has become, in spite of himself, the father of dispute. Another reputation which has been wrongfully acquired is that of genial innovator. In reality, by temperament and training, he was an inveterate conservative and, in a certain sense, even a restorer, as one can see in the Acts of the Roman Synod and also in the first schemas of Vatican II. In short, these documents were far more oriented towards a recapitulation of the traditional ideas, in a modern style and sensibility, than towards the presentation of radically new ideas. In addition, the novelties did not spring forth from the merits or demerits of the Bishops, but rather from the experts who were the true artisans of Vatican Council II. These latter, well prepared and well coordinated, knew how to maneuver so cleverly that there remained almost nothing of the original schemas, those that we could call Johannine. (For the details, we return to the book by Fr. Ralph Wiltgen, already cited). As the reader will have perceived, our indictment does not concern certain tiny faults of John XXIII, such as could be found in any saint. It deals rather with a style of life and of government too inclined towards the desire to please and towards attracting universal sympathy and good will. Too much of the behavior of "the good Pope" was not that of a good pope. Some will object: it is just a matter of mistakes in "technique," which does not invalidate the subjective sanctity. We reply that the true goodness of one who governs must constantly be regulated by the prudence proper to those who govern, which, in its turn, must be sustained by the virtue of fortitude, given the requisite inter-connection of all the virtues. Moreover, the future pope was aware of this weak side of his nature. Molinari observes that this is brought out in Roncalli's book Journal de l’Ame, where he promises "not to give way too much to his peaceful and easy going temperament" (p. 139, Molinari, op. cit.). But, just as he never succeeded in correcting his fault of excessive loquacity, neither was he able to fortify himself with the strength of soul needed to govern the Church and not to allow himself to be governed, thereby handing on to his successor a very difficult heritage.

PAPAL SANCTITY IS A VERY DIFFICULT SANCTITY Even though the Pope is given the title His Holiness, it is difficult to be holy in that position, because the duties are so serious, so complex and often almost contradictory. It is not insignificant that John XXIII did not believe in the sanctity of Pius XII, as was reported to me by a very highly authorized member of the Holy Office. This source added that when Pope John went down into the Vatican Grotto to make a visit to the tomb of his predecessor, he very openly said a De Profundis, to make known to those around him that he did not consider Pope Pius XII canonizable, and, thereby, to put a brake on the movement which was already appearing. The Pope himself explained to him the signification of his prayer for the dead. That which for others (including the Postulator of the cause for Roncalli) is exquisite virtue, is for me (the undersigned) a vice, if it is erected into an accepted system of governing; a very grave and dangerous vice! But one could object that "the good Pope" did not always allow himself to be guided by the desire to please...and one could cite some of the vigorous gestures of reprobation enumerated by Molinari on p.164 (op. cit.). But, aside from the fact that certain of them have been exaggerated, such as the "Spiazzi case" for example, they were momentary outbursts of his visceral traditionalism and of his not very costly adhesion to the Curial program quieta non movere, Not to change things which are peaceful...If he had been able to foresee, and he should have been able to foresee at least in part, the development and the consequences of Vatican Council II, I think that he would never have convoked it. But in the matter of prevision, though many have called him a prophet, Pope Roncalli was rather lacking, as Carlo Falconi demonstrates so well in his inquisitive book (op cit.). From the testimony of his confessor, Msgr. Cavagua, I know that the Pope, in the last moments of his life, was very distressed to see how things were developing on the ecclesiastical and the political levels. There should have been less good nature and more constancy. On this point there comes to mind the long and ferocious critique that Nietzsche makes of the good man (he should have said of "the good-natured man") in his posthumous Fragments:

For the German philosopher, this type of man is the most noxious. He continues...

It is precisely these good and conciliatory people who become dangerous when placed in positions of authority, because they are easily manipulated by those who are stronger and more deceitful than they are. However, that is not exactly Nietzsche's perspective when he says that the good are harmful. To understand his paradoxical affirmations, one must place them within the concepts of the "super- man" and of the "will to dominate." Obviously, we do not subscribe to them, except in the curtailed sense of the popular saying:

Here is how Ernest Hello describes the kindly doctor (who is, naturally, anything but a good doctor):

Hello, himself, in this context, makes allusion to the danger of compromise in the matter of teaching. He had in fact written a bit before:

There is in the same work an amazing passage in which he de- scribes the type of saint that the world would desire; and, on the matter of saints, it is the author of Physionomies de Saints whose voice is heard here. This passage throws a beam of light on the universal sympathy that Pope Roncalli evoked even among men of the world, although, let it be well understood, his moral character only coincided in a very reduced proportion with that of the model described by Hello:

It affirms then that you resemble Jesus Christ, who pardoned sinners. Among all the confusion that the world cherishes, here is the one that it most greatly cherishes: it confuses pardon with approbation. Because Jesus Christ pardoned many sinners, the world wants to infer that Jesus Christ did not greatly detest sin (E. Hello, L'Homme II; Les Alliances Spirituelles, Montreal, pp.197 ff). We come at last to the end of these bitter disputes and harsh considerations, (imposed by suffering in face of the decay which devastates the Church in the domains of the faith, of practices and of discipline); in the presence of the frightful crisis of vocations, of the numerous defections of priests and religious, of the advance of atheistic communism - all of which evils derive, at least in part, from the lack of firmness and clear-sightedness in the pontifical governance of John XXIII. I can easily imagine what a wave of indignation is going to arise from those who are unreserved admirers of Pope Roncalli. In my partial exoneration, I will say that while the now-deceased Pope, "in order to please everyone," did not always brutally speak the truth, or, more correctly, that which he thought, the undersigned, on the contrary, by temperament and conviction, judges it expedient to manifest his thought harshly, even at the price of displeasing many, while however remaining prompt to retract if it is shown to him that he is wrong, since no one is infallible, especially in matters of history and the more so when it is a matter of very recent events. P.

Innocenzo Colosio, O.P.

Courtesy of the Angelus

Press, Kansas City, MO 64109 |