![]()

![]()

|

May 1999 No. 32

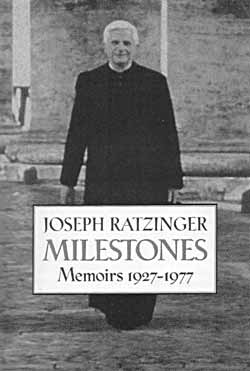

In 1996, Cardinal Ratzinger published an in-depth interview of himself titled Salt of the Earth1 and in 1997 an autobiography called Milestones: Memoirs 1927- 1977.2 These books are important if we consider the high post the Cardinal holds in the Vatican. In this second article (Part I appeared in The Angelus, March, 1999), we continued our review of Milestones to better understand the current crisis in the Catholic Church.

A NOVEL NOTION OF TRADITION There is a need, therefore, to be on guard: When Cardinal Ratzinger defends the Catholic position against the "sola scriptura" of the Lutheran heretics, it is necessary to pay attention to what he means by "revelation" and "tradition." In the passage from Milestones in which he rebuts the criticism that seminary professor Schmaus had levied against him earlier, Cardinal Ratzinger establishes, in fact, as we have seen, a link between revelation and tradition, but he does so in the light of the subjective concept of revelation that he professes. He writes that "an essential element of Scripture is the Church as understanding subject, and with this the fundamental sense of tradition is already given" (p.109). How is this affirmation to be understood? It must be taken according to the notion of revelation which we have seen earlier (see SISINONO, March 1999). He is not talking about the Church which, aided by the Holy Ghost, keeps the deposit of revealed truth unchanged down the ages, explaining it, indeed, but without the power to alter it by a jot or tittle. What he does mean, on the contrary, is the Church which, taken as "understanding" or "perceiving" subject, is necessary for revelation to exist. He means the Church conceived as subject, which for that reason becomes a constitutive element of revelation by taking possession of it, and plays an active, creative role in its relation to revelation. Under this perspective, the Church's tie to revelation means that Scripture depends upon the Church as "knowing subject" in order to be Revelation. The Cardinal writes, in fact, that Revelation "is not simply identical” to Scripture, it is always greater than "what is merely written down" (op. cit., ibid.). Note, though, that what is outside Holy Scripture is not, according to the Cardinal, provided by oral tradition ("sine scripto traditiones"). To highlight this fact, compare his notion to what was set forth by the Council of Trent and reiterated by Vatican I. Of tradition it is said that the Church "holds...also the traditions themselves, those that appertain both to faith and to morals, as having been dictated either by Christ's own word of mouth, or by the Holy Spirit, and preserved in the Catholic Church by a continuous succession" (Denzinger, The Sources of Catholic Dogma, 783). And from the same place: "...[p]erceiving that this truth and instruction are contained in the written books and in the unwritten traditions, which have been received by the apostles from the mouth of Christ Himself, or from the apostles themselves, at the dictation of the Holy Spirit, have come down even to us, transmitted as it were from hand to hand ….…" Not so, according to the Cardinal. For him, what is not contained in Sacred Scripture is not given objectively by tradition, as that has always been understood and defined by the Church through the centuries. On the contrary, it is given by the "understanding subject" (the Church) which, making up a part of Revelation as an essential constitutive element, relies only upon itself (and hence on its history or evolution from the "primitive community of believers") for its determination of the truth of Revelation itself. So, according to the point of view expressed by the Cardinal, the "essential meaning to be given to tradition" is not the result of an immutable truth revealed by God, but results from the truth which the "perceiving subject" constitutes in Revelation in an historically gradual, progressive way because the development of the "receiving subject" in its own self-awareness is gradual and progressive. The notion that truth only exists thanks to the thinking subject, who imparts truth to its object, is necessarily associated with the other powerful notion in secular thought: that of progress, understood as progress in consciousness...and which can never have, resting as it does on such a basis, a final term or transcendent goal. The will to introduce into the concept of Revelation the notion that the subject to whom it is addressed constitutes the message's meaning, leads necessarily to a corruption of both concepts, Revelation and Tradition. Revelation is no longer taken as a self-contained body of events and teachings of exclusively supernatural origin, which the subject for whom it is destined - for the salvation of whom these "deeds and values" have been revealed - must accept and keep without any alteration whatsoever, because he finds himself presented with truths which do not depend upon himself, but which come from God. Likewise, tradition is falsified by this conception, because it no longer expresses the idea of a "deposit of Faith" divine in origin, kept for 19 centuries and resulting from Scripture and Tradition preserved and taught by the Church's magisterium. It no longer signifies a "depositum" to which no new interpretation can be given. On the contrary, this new notion of tradition expresses an idea that is not Catholic. Rather, it has a secular and Protestant origin. It is the idea that the Church, as receiving subject, even as it constitutes essentially and by degrees the truth of Revelation, equally constitutes by degrees the truth of tradition in the framework of a process, of which one can see no end "ad quem," and which has no other point of reference than the consciousness that the Church is supposed to have of itself, a Church which examines itself by using the categories which come from profane philosophies (Kant, Heidegger, and the like, instead of St. Thomas Aquinas). The effect of this rethinking came to the fore at Vatican Council II, when we saw a new definition of the Church given, a definition that contradicts what the Church herself has taught (by her true tradition) for 19 centuries. We are referring to the notorious "subsistit in" of Lumen Gentium §8, according to which the Catholic Church is no longer the one and only Church of Christ, but that it subsists in her in the same way as in other entities capable of leading to salvation (the so-called "separated brethren" and perhaps even the non-Christians). Cardinal Ratzinger himself confirms, in the above-cited passage, that during the debates at the Council on the topics of Revelation, Scripture and Tradition, he contributed to this new understanding. The ultimate result of this change is to be seen in the theological and liturgical chaos currently prevailing in the Church.

AN IRRATIONAL NOTION OF TRADITION Tradition thus understood is also presented as a "living process" of the Church, which "becomes history" by opening towards new understandings and which is opposed to the idea of Revelation held by neo-scholastic intellectualism, which would merely be the product of the "pre-fab" logic of St. Thomas. Cardinal Ratzinger uses this concept of "development" when he recounts the opposition which the Theological Faculty of Munich formulated against the proclamation of the dogma of the Assumption. The opposition was based on the affirmation of an "expert," Professor Altaner, patrologist, according to whom "the doctrine of Mary's bodily Assumption into heaven was unknown before the fifth century; this doctrine, therefore, he argued, could not belong to the ‘apostolic tradition'" (op. cit., p.58). The affirmations of the specialist in question are contested, and can also be explained by the desire, which was then quite keen in certain Catholic circles, to enter into the good graces of the Protestants, notoriously hostile because of their heresy concerning the person and the cult of the Blessed Virgin. Cardinal Ratzinger observes that, in this case, Professor Altaner was using a restricted conception of tradition, because, in fact, "they were identifying tradition and textual proofs." How then does Cardinal Ratzinger justify the dogmatic definition given by Pope Pius XII? with, perhaps, the same arguments which Pope Pius XII used to justify it, namely, that the Assumption of the holy Mother of God is a truth that has always been believed and taught by the Church, since, in the writings which have come down to us, the holy Fathers and ecclesiastical writers have spoken of it, not as something new, but ''as a truth supported by Sacred Scripture and which is rooted in the hearts of the faithful” (Dogmatic Bull Munificentissimus Deus)? Not by a long shot. Here is the Cardinal's argument: But if you conceive of "tradition" as the living process whereby the Holy Spirit introduces us to the fullness of truth and teaches us how to understand what previously we could still not grasp (cf. Jn. 16:12-13), then subsequent "remembering" (cf. Jn. 16:4, for instance) can come to recognize what it had not caught sight of previously and yet was already handed down in the original Word (op. cit., p.59). In this passage, tradition is defined as "a living process" of which the Holy Ghost is the artisan. The "process" therefore is not linked to texts or even facts. Tradition, according to the Catholic meaning of the word, however, has never been understood as a process or a reality detached from facts (which is what the dogmatic definition of the Assumption demonstrates). The idea of "process" contains the idea of truth which develops by degree thanks to the thinking of man, and this development is here attributed to the Holy Ghost. The Holy Ghost would be operating as the pedagogue of the "understanding subject," and would act gradually by keeping Revelation open! The Catholic notion of tradition, on the contrary, contains the idea of conservation, of the transmission of the deposit of the Faith which has been given once and for all (cf. Jude, v.3), against every possible novelty or subsequent contradictory development. In the case of the Assumption, they were faced with a fact: the cult which, from the origin of Christianity, professed the bodily assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into heaven, and included the veneration of her empty tomb (which is, even to this day, guarded by Christians, albeit the Orthodox). The question was whether to sanction this faith by a dogmatic definition. The fact was the same for 19 centuries, a mystery of Faith continuously and universally professed by the faithful. It had nothing to do with some "process" or "development." The dogmatic definition of the Assumption has no need to be seen as the expression of a "vital process," which succeeded by degrees in creating a new content of faith, which for a long time had been certified by witnesses and felt to belong to dogma. No novelty was introduced. What the Cardinal writes when he says "subsequent 'remembering' can come to recognize what it had not caught sight of previously and was already handed down in the original Word," does not seem to us to fit the case. Here there is no question of "subsequent remembering" because the belief in the Assumption has always existed. It has always remained constantly living and efficacious. For this same reason - the perpetuity of this faith and this devotion - it is certainly not possible to speak of something "not caught sight of previously." The fact is that Cardinal Ratzinger, even as he criticizes Professor Altaner, seems to justify him by speaking of a "subsequent remembering," that is to say, something fabricated" post festum." Later on, even if he judges him to have been wrong and justifies the definition of the Assumption, he does so on the basis of its being the expression of the "living process" which, according to him, is of the essence of tradition; he accepts it, that is, as an expression of the creativity of the Church, "receiving subject" (and hence constitutive) of Revelation. The Church would be, it seems, a theologian who constructs Revelation in the same manner as did the first "primitive community."

A "NEW EXEGESIS" FOR THE "NEW THEOLOGY"

The interpretation of this dogmatic declaration, as everyone can see for himself, is rather peculiar. In fact, it presents the typical traits of the New Theology. The Cardinal's theology is not Catholic theology; it is the new theology because it makes the supernatural depend upon man's own thought in order to keep Revelation open. It is not for nothing that he was profoundly influenced - as he himself recognizes - by Henri de Lubac! In commenting on this passage, it is necessary to add that Cardinal Ratzinger's justification of his argument concerning the role of the Holy Ghost is not supported by the Scripture passages to which he refers. The first is the text in which the Lord announces to the apostles that "the Spirit of truth...will teach you all truth,“ even “things that are to come.” We do not believe this “teaching,” which also includes prophesy, applies to the case at hand. The second text contains an announcement even more specific, which surely does not apply here. It is when He is announcing to them ahead of time the persecution they will suffer at the hands of the Jews. The Lord says to them: “But these things I have told you, that when the house shall come, you may remember that I told you of them” (Jn. 16:4). The "remembering" of which St. John speaks does not refer to past facts, but is linked to future events: it is linked to the prophetic announcement of the coming persecution for the faith: You will remember tomorrow, Jesus says, what I am telling you today! You will remember a specific event that took place before witnesses. It has absolutely nothing to do with the "living process" or nebulous "remembering" mentioned by the Cardinal, notions which, taking their origin in the "existential philosophies" of laymen and literature, fade into something indeterminate, and which, in any case, display not only a completely irrational notion of tradition, but also one that is completely foreign to true Catholic theology - which is certainly not the theology of the liberal and modernist masters from whom Ratzinger has constantly drawn his inspiration.

APOLOGIA PRO DOMO Another essential aspect of Cardinal Ratzinger's autobiography is his attempt to disown any responsibility for the modernist deviations that followed upon Vatican II. During the Council, he was the theological advisor of Cardinal Frings, Archbishop of Cologne, one of the prominent representatives of the progressive wing, who had chosen him for this delicate and important task precisely because of the "modern" orientation of his theology. Young Professor Ratzinger, then just 30 years old, took part in the Council from the inside, aligned with the most radical progressive theologians (the Rahners, de Lubacs, Congars, etc.), those forming the "Rhone Alliance." In his memoirs he seeks to downplay his participation in this "Sodalitium." He writes that "the theological and ecclesial drama of those years [does not] belong in these memoirs" (p.121), but he makes exception in order to comment upon certain questions about which he clearly wishes to make a few points. THE PREPARATORY SCHEMAS We learn that Joseph Rat zinger was not in favor of rejecting all the preparatory schemas, rejection which marked the first manoeuver of the progressives at the Council. He

[Cardinal Frings] now began to send me these texts regularly

in order to have my criticism and suggestions for improvement.

Naturally I took exception to certain things, but I found

no grounds for a radical rejection of what was being proposed.

It is true that the documents bore only weak traces of the

biblical and patristic renewal of the last decades, so that

they gave an impression of rigidity and narrowness through

their excessive dependency on scholastic theology. In other

words, they reflected more the thought of scholars than

that of shepherds. But I must say that they had a solid

foundation and had been carefully elaborated" (p.121).

THE LITURGY On the question of the liturgy, the Cardinal seeks to defend the Council by maintaining that the prevailing orientation was not especially revolutionary. His defense of the Council on this point rests upon the following argument: no one then could have foreseen the subsequent subversive and revolutionary developments of the liturgical reform, developments which were not justified (according to him) by the texts approved by the Council. I became a partisan of the liturgical movement at the beginning of the Council...I saw in the elaboration of the Constitution on the Liturgy, which incorporated all the essential discoveries of the liturgical movement, a magnificent start for the Church assembly, and I counselled Card. Frings accordingly. I could not foresee that the negative aspects of the liturgical movement would reappear more vigorous than ever, leading straight to the self-destruction of the liturgy. According to the Cardinal, then, the Council approved, without having well calculated the dangers, a document that was going to allow the negative developments which we well know and which are still at work. The Cardinal says that neither he nor others could foresee it. Yet, according to the Cardinal's own ideas, a conciliar document should be understood as the expression of the "living process" directed by the Holy Ghost, which for him is the essence of tradition. One wonders how this "living process" could have been suddenly stricken by a spontaneous, long-term necrosis. If the conciliar document on the liturgy indirectly contributed to the negative effects which followed, this would mean that it contained ambiguities or dangerous laxities. Is it to be thought, then, that the drafting of this text, which directly or indirectly is not good (because, one way or another, it has served as a cover for the "auto-destruction" of the liturgy), was inspired by the Third Person of the Most Blessed Trinity? We also find another demonstration of the way in which the Cardinal's concept of tradition was not Catholic: the creativity of the Church, constitutive subject of Revelation, which is actualized by degrees in the course of "salvation history," would have allowed initiatives which have shown themselves to be disastrous, because they have allowed the ruination of the liturgy. In fact, the preparatory schema on the liturgy was the only one not rejected by the progressives who dominated in the Council, but only because it had already been corrupted by the "essential conquests of the Liturgical Movement, " that is to say, by a manner of understanding the liturgy which only initially fits into Catholic tradition. The question of the liturgy justifiably occupies the thoughts of the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Confronted with the prevailing liturgical chaos, what can be the remedy? Most certainly, he avoids highlighting the theologically ambiguous character of the Mass of Pope Paul VI, which is one of the principal causes of the current chaos. Nonetheless, in his Milestones, there is a telling page on the topic, concerning the promulgation of the Novus Ordo Missae of Pope Paul VI. The Cardinal declares himself to be "dismayed by the prohibition of the old missal, since nothing of the sort had ever happened in the entire history of the liturgy" (p.146). (The fact is that the Missale Romanum codified by Pope St. Pius V was never prohibited by Pope Paul VI.) In any case, Cardinal Ratzinger recounts the truth concerning the missal of St. Pius V, which was not created by this Pope, for it was not a new missal. Faced with Protestant infiltrations into the liturgy, in 1570, Pope St. Pius V: ...decided that now the Missale Romanum - the missal of the city of Rome - was to be introduced as reliably Catholic in every place that could not demonstrate its liturgy to be at least two hundred years old….The prohibition of this missal that was now decreed,...introduced a breach into the history of the liturgy whose consequences could only be tragic…[T]he old building was demolished, and another was built…[T]his has caused us great harm (op. cit., p.148). His remarks are quite true. What is to be done? A renewal of liturgical awareness, a liturgical reconciliation that again recognizes the unity of the history of the liturgy and that understands Vatican II, not as a breach, but as a stage of development: these things are urgently needed for the life of the Church. I am convinced that the crisis in the Church that we are experiencing today is to a large extent due to the disintegration of the liturgy, which at times has even come to be conceived of etsi Deus non daretur…Then the community is celebrating only itself, an activity that is utterly fruitless…This is why we need a new Liturgical Movement, which will call to life the real heritage of the Second Vatican Council (ibid.). After making a substantially correct analysis, Cardinal Ratzinger comes to a disconcerting conclusion: what is needed is a new "liturgical movement," one that will "call to life the real heritage of the Second Vatican Council"! He cannot let go of Vatican II, which would appear to be the anchor of salvation. The solution is not to go back to the genuine tradition of the Church; no, it is necessary to return to the real Vatican II, whose authentic meaning has still not been understood! The Cardinal does not know how to think in terms other than evolution towards the new: Vatican II must not be seen as a break with tradition (which, in fact, it was) but rather as a "moment of evolution," a stage of development. Pressed to identify the term of the development, the answer is, towards something new, and in this particular case, towards a "new liturgical movement." The "liturgical reconciliation" of which he speaks does not in any way express a recognition of the rights of the true Catholic tradition. It means, on the contrary, reconciliation with Vatican II, by allowing the genuine innovative development (which is, of course, not the same as that of the destroyers of the liturgy) thanks to a new liturgical movement! We must "return" to the (merely pastoral) Council which denied, in black and white, that the Catholic Church is the one Church of Christ, the one ark of salvation! We must return to the Council, which sought to establish the truth of religion on individual liberty of conscience, and not on revealed truth! We must "return" to the Council, which sought to deny the responsibility of the Jews in the crucifixion of the Lord, in contradiction to the categoric testimony of the Gospels. The solution would be a new liturgical movement, as if the horrific errors of the first one were not enough. It is quite possible that the encouragement given by the Cardinal to the charismatic movements which are daily making inroads in the Church by infecting it with a corrupt spirituality originating in the worst Protestant sects (Quakers, Pentecostals, etc.) should be seen in the light of an attempt to give rise, whatever it may take, to "a new liturgical movement." These remarks describing the Council as a "stage of development" and a "new movement" which would complete the process show that we are witnessing a recrudescence of progressive vigor .

THE COUNCIL

Finally, our author repeats almost as a refrain that Vatican II has not been understood. Concerning the document Dei Verbum, the Constitution on Divine Revelation, he says that it "has yet to be truly received." In general, "we still have before us the task of communicating what the Council actually said to the Church at large and, beyond that, of developing its implications" (ibid, p.129). So, 32 years after the Council's closure, they tell us that it has still not been properly understood and that it is necessary to rediscover its authentic meaning. It remains to ask how the Council has not been understood, and by whose fault. The Cardinal places himself in parallel with the Council: just as the latter has not yet been understood, neither has he. We have seen that he was not in favor of the progressives' integral rejection of the preparatory schemas. Moreover, we learn that his own opposition to the official schema on the Sources of Divine Revelation has not been correctly appreciated either, because actually he had wanted to express the concept of Revelation he holds to be in harmony with tradition. Just as at the time when he was defending his doctoral thesis, his thinking had not been understood by Professor Schmaus, so also, the Cardinal maintains, it was not well understood at the Council. He was filled with consternation by the increasingly revolutionary development at the Council: The impression grew steadily that nothing was now stable in the Church, that everything was open to revision. More and more the Council appeared to be like a great Church parliament that could change everything and reshape everything according to its own desires. Very clearly resentment was growing against Rome and against the Curia, which appeared to be the real enemy of everything that was new and progressive. The disputes at the Council were more and more portrayed according to the party model of modern parliamentarism….For believers, it was a remarkable phenomenon that their bishops seemed to show a different face in Rome from the one they wore at home. Shepherds who had been considered strict conservatives suddenly appeared to be spokesmen for progressivism. But were they doing this all on their own? The role that theologians had assumed at the Council was creating ever more clearly a new confidence among scholars, who now understood themselves to be the truly knowledgeable experts in the faith and therefore no longer subordinate to the shepherds….But now in the Catholic Church all of this - at least in the popular consciousness - was up once again for revision, and even the Creed no longer appeared untouchable but seemed rather subject to the control of scholars. Behind this tendency to dominance by specialists one could already detect something else: the idea of an ecclesial sovereignty of the people in which the people itself determines what it wants to understand by Church... (ibid, pp.132-134). Cardinal Ratzinger effectively evokes the terrible spirit of revolutionary agitation which at a certain point seized the majority of the Council members, and, without intending it, he confirms the remark that Archbishop Lefebvre made, that, at a certain point, Satan had taken hold of the Council. The will to change everything, the mania for novelty at any price born of hatred against the principle of authority, against Rome and the institution of the papacy: Were we to conclude that such things were inspired by the Holy Ghost? They could only come from the Devil. The agitation which took possession of the Church then has still not abated; moreover, it is hard to imagine what pressure from the Vatican or what authority could effectively curb bishops and theologians today. Concerned by the direction events were taking, Ratzinger, at a conference held at the University of Munster, "tried to sound a first warning signal, but few if any noticed" (p.134). He was even so insistent in the remarks he delivered at the Catholic Day held at Bamberg in 1966 that Cardinal Dopfner was "astonished" by the "conservative accent" that he perceived (ibid). On the basis of these incisive declarations, the Cardinal places himself on the side of those who, in the terrible post-conciliar period, "had redefined their positions," concerned for the future of the Faith. But, let us note, for him, there was no question of "redefining" his position: From the moment when he claimed that he had not been well understood, that is to say, from the time of his study of the writings of St. Bonaventure, there has been no change. It is clear that Cardinal Ratzinger considers that his position in the post-conciliar period, and even now, is substantially the same as the one he held as a researcher when he was accused (and quite rightly) of wanting to elaborate a subjectivist conception of Revelation. What is striking is that in this autobiography, there is no self-criticism: those who accused him of being a liberal and a modernist simply have not understood his thinking. Likewise, those who accuse Vatican II because of the disastrous situation in the Church which has resulted also have not understood Vatican II. Or rather, the history - and the analysis - of Vatican II are yet to be accomplished.

CONCLUSION His remarks come across as a fastidious apologia. Cardinal Ratzinger seems to have learned nothing from all that has happened. He is only concerned with showing the continuity of his theology, believing that by so doing he is defending both himself and Vatican II. From this defense a certain image of Cardinal Ratzinger as restorer of the Faith has been created; and it is an image in which many still believe. However, it is only blatant mystification. The best known work of the Cardinal is the book, Introduction to Christianity, published in 1968 and translated into 17 languages. He speaks of it with satisfaction. Not withstanding, the Christology that he sets forth is scarcely orthodox. Sometimes he only very narrowly avoids the theology of heretics, which has been passively absorbed by the majority of Catholic theologians. He also affirms that Jesus the Messiah is a product of the faith of the primitive community: "He is the One who died on the cross, and Who, to the eyes of faith, rose" (Italian ed., Brescia, 1971, 4th ed., p.171) .The Resurrection is not then an historical fact, but a simple belief of the disciples. Like examples from the book could be multiplied. The reputation of Ratzinger as restorer of the Church does not rest on his works. It is probably owing to the fact that several times he has quite clearly described certain disorders, and that he has always dissociated himself from the most extreme factions. But this takes away nothing from the modernist foundation of his theological vision: "Ratzinger is always like that: To counter the excesses, from which he keeps his distance, he never proposes Catholic truth, but rather an apparently more moderate error, which, nevertheless, in the logic of error, leads to the same ruinous conclusions" (SISINONO, no.6, 1993, p.6). Some commentators have compared the Second Vatican Council to the Estates General of the French Revolution. Developing the analogy, one might say that Cardinal Ratzinger is a Girondist. The members of that faction were certainly more politically moderate than were the Jacobins, and especially their left wing (to which, in theology, we could compare the Kungs, Drewermanns, etc.), but they were no less revolutionary. They wanted to accomplish the same objectives, only in a more gradual, pragmatic manner. Their vision of the world, though, was identical: human reason exalted and placed in the center of the universe, democracy, bourgeois individualism; identical, too, was their hatred of Christianity, their desire to confiscate the goods of the Church, etc. Neither his autobiography nor his book-length interview shows us a Ratzinger different from the one we have known. We can only hope for a miracle, that he might one day soon decide to become an effective Prefect for the Doctrine of the Faith, and intervene authoritatively according to the Church's own theology (and not his own personal one) against the Reign of Error which has been installed in the Catholic world for too long. Aegidius (Translated from Courrier de Rome, December 1998)

The SiSiNoNo article reviewed by Bishop Richard Williamson in his monthly Letter to Friends and Benefactors (April 2, 1999) will appear here in its English translation starting in July, 1999. 1. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Salt of the Earth; The Church at the End of the Millennium, an interview with Peter Seewald (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1997). Cited passages are taken from this English language version. 2. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, Milestones; Memoirs 1927-1977(SanFrancisco: IgnatiusPress, 1998). Passages cited refer to this English language version.

Courtesy of the Angelus

Press, Kansas City, MO 64109 |