|

Newsletter of the District

of Asia

January

- February 2000

The

Graffiti Wall

The bones of Saint Peter

By

J.E. Walsh

Second

Part

"

The first part of this article appeared in the Newsletter of September-

October 1999 January - February 2000"

As

Vatican II was coming to a close in 1965, so was the identificatino

of the Bones found underneath the Main Altar in St. Peter's, in

the Vatican. Providence was clearly indicating that it was truly

on St Peter that the Catholic Church was built and that real Catholic

apostolate had to bring souls into the roman Church, and not let

them live apar from it as is being done today with inculturation.

The mind behind the discovery of the actual bones of St Peter was

Dr. Guarducci.

ER

REQUEST for permission to make a study of intriguing tangle was

quickly honored, but she was delayed for a while by some other commitments,

and by the writing of a report on the Valerius epigraph. It was.

September 1953 before she was able to begin. ER

REQUEST for permission to make a study of intriguing tangle was

quickly honored, but she was delayed for a while by some other commitments,

and by the writing of a report on the Valerius epigraph. It was.

September 1953 before she was able to begin.

When

for the twentieth time her magnifying glass moved across the upper

left corner of the graffiti wall, there suddenly leaped out at her,

just above a Christ monogram, five letters arranged in two lines

As her first move at the graffiti Christ monogram, wall, Dr. Guarducci

arranged for a series of professional photographs to be taken of

the whole surface, overlapping close-ups which would capture every

nuance of the inscriptions. Spending hours each day at the wall,

usually kneeling on a cushion, one hand holding a light while the

other wielded the magnifying glass, she was soon oblivious to the

passing hours. As the days went by she fell into a steady rhythm.

Spending mornings at the basilica, then continuing her studies with

the photographs at home in the afternoons, the only break in the

routine coming from her teaching duties at the university. There

were also frequent visits to the libraries and museums of Rome as

she searched for any smallest light that might be thrown on the

scratches by the work of the other scholars in related fields. When

for the twentieth time her magnifying glass moved across the upper

left corner of the graffiti wall, there suddenly leaped out at her,

just above a Christ monogram, five letters arranged in two lines

As her first move at the graffiti Christ monogram, wall, Dr. Guarducci

arranged for a series of professional photographs to be taken of

the whole surface, overlapping close-ups which would capture every

nuance of the inscriptions. Spending hours each day at the wall,

usually kneeling on a cushion, one hand holding a light while the

other wielded the magnifying glass, she was soon oblivious to the

passing hours. As the days went by she fell into a steady rhythm.

Spending mornings at the basilica, then continuing her studies with

the photographs at home in the afternoons, the only break in the

routine coming from her teaching duties at the university. There

were also frequent visits to the libraries and museums of Rome as

she searched for any smallest light that might be thrown on the

scratches by the work of the other scholars in related fields.

To

her great consternation, the first weeks of this intensive effort,

in which she tried one hypothesis after another while calling on

her while store of epigraphical knowledge, yielded exactly nothing.

Behind the enigmatic jumble she could discern no rationale, no pattern.

No ghost of a personality became visible. Only here and there could

she find some letter - an A, a B, an E - which appeared to separate

itself from its surroundings. Or were these forms mere accidents

of conjunction? Of even this she couldn't be certain, and when a

whole myth fled by without the least hint of progress, in desperation

she began casting around for something, anything, some stray bit

of information, that might afford even the slightest clue to the

wall's stubborn secret. To

her great consternation, the first weeks of this intensive effort,

in which she tried one hypothesis after another while calling on

her while store of epigraphical knowledge, yielded exactly nothing.

Behind the enigmatic jumble she could discern no rationale, no pattern.

No ghost of a personality became visible. Only here and there could

she find some letter - an A, a B, an E - which appeared to separate

itself from its surroundings. Or were these forms mere accidents

of conjunction? Of even this she couldn't be certain, and when a

whole myth fled by without the least hint of progress, in desperation

she began casting around for something, anything, some stray bit

of information, that might afford even the slightest clue to the

wall's stubborn secret.

From

the strange embroidery on the graffiti wall, under Dr. Guarducci's

questing stare some fifty names eventually emerged, distinct and

separate, all of them familiar in third and fourth-century Roman

usage. About half were linked to a Christ monogram, and about a

third included prayers and invocations, always abbreviated, wishing

for the dead eternal joy in Christ. But even after isolating all

these names and phrases, often by minutely tracing out individual

letters in succession, there still remained the weird inundation

of extra lines from which no sense could be extracted. From

the strange embroidery on the graffiti wall, under Dr. Guarducci's

questing stare some fifty names eventually emerged, distinct and

separate, all of them familiar in third and fourth-century Roman

usage. About half were linked to a Christ monogram, and about a

third included prayers and invocations, always abbreviated, wishing

for the dead eternal joy in Christ. But even after isolating all

these names and phrases, often by minutely tracing out individual

letters in succession, there still remained the weird inundation

of extra lines from which no sense could be extracted.

Further

weeks of fruitless study passed, then months, and despite the many

fatiguing hours she spent on her knees before the wall, or bent

over the pile of photographs at home, her bafflement continued to

deepen. Earnest discussion of the vexing problem with her sister,

with colleagues at the university, and with Pope Pius himself, brought

sympathy and encouragement but no real assistance. Once during those

months, however, her efforts were rewarded with a discovery and

though it proved of no assistance in deciphering the other scratches,

in its own way it was electrifying. Further

weeks of fruitless study passed, then months, and despite the many

fatiguing hours she spent on her knees before the wall, or bent

over the pile of photographs at home, her bafflement continued to

deepen. Earnest discussion of the vexing problem with her sister,

with colleagues at the university, and with Pope Pius himself, brought

sympathy and encouragement but no real assistance. Once during those

months, however, her efforts were rewarded with a discovery and

though it proved of no assistance in deciphering the other scratches,

in its own way it was electrifying.

|

|

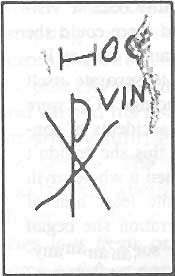

Fig.

1

|

When

for the twentieth time her magnifying glass moved across the upper

left corner of the graffiti wall, there suddenly leaped out at her,

just above a Christ monogram, five letters arranged in two lines

(see Fig. 1): When

for the twentieth time her magnifying glass moved across the upper

left corner of the graffiti wall, there suddenly leaped out at her,

just above a Christ monogram, five letters arranged in two lines

(see Fig. 1):

At

their right edges both lines ran into broken plaster and could thus

have once been longer. In fact, the ragged form of what might have

been a C still clung vaguely to the end of the first line. Instantly

Dr. Guarducci recognized the phrase for what it was, the only thing

it could be: IN HOC VINCE, Latin for "In this, conquer."These

very words, she knew, had formed part of Constantine's famous aerial

vision in the year 312, just before his final battle for home. In

the vision, the words had been accompanied by some unspecified type

of cross, and the Emperor had jubilantly ordered his troops to paint

the emblem on their shields and helmets. A rapid victory had followed. At

their right edges both lines ran into broken plaster and could thus

have once been longer. In fact, the ragged form of what might have

been a C still clung vaguely to the end of the first line. Instantly

Dr. Guarducci recognized the phrase for what it was, the only thing

it could be: IN HOC VINCE, Latin for "In this, conquer."These

very words, she knew, had formed part of Constantine's famous aerial

vision in the year 312, just before his final battle for home. In

the vision, the words had been accompanied by some unspecified type

of cross, and the Emperor had jubilantly ordered his troops to paint

the emblem on their shields and helmets. A rapid victory had followed.

|

|

The

excavations beneath St. Peter's

|

As

it happened, the earliest report of this memorable incident was

a contemporary one, written down from Constantine's own lips by

the historian Eusebius. In his short account, and almost as an afterthought,

Eusebius had also preserved the vital fact that the Emperor had

not been the only witness to the arresting sight: "He said that

with his own eyes, during the afternoon, while the day was already

fading, he had seen a shining cross in the sky, more brilliant than

the sun, accompanied by the words, `In this, conquer.' He remained

stunned by the vision, and so did all the army following him in

the expedition, which had also seen the miracle:" As

it happened, the earliest report of this memorable incident was

a contemporary one, written down from Constantine's own lips by

the historian Eusebius. In his short account, and almost as an afterthought,

Eusebius had also preserved the vital fact that the Emperor had

not been the only witness to the arresting sight: "He said that

with his own eyes, during the afternoon, while the day was already

fading, he had seen a shining cross in the sky, more brilliant than

the sun, accompanied by the words, `In this, conquer.' He remained

stunned by the vision, and so did all the army following him in

the expedition, which had also seen the miracle:"

The

marvel had quickly become an accepted part of church history and

had remained so, unquestioned, for many centuries. More recently

there had arisen a tendency among scholars to question its factual

basis. The

marvel had quickly become an accepted part of church history and

had remained so, unquestioned, for many centuries. More recently

there had arisen a tendency among scholars to question its factual

basis.

(to

be continued)

|

![]()

![]()