![]()

![]()

|

Newsletter of the District of Asia November - December 2000 Set All Afire! St Francis Xavier and Japan By Louis de Wohl

Book Five(…) In the meantime Father Francis had a marriage to perform. A young officer of the triumphant fleet married a charming half-caste girl. There were clusters of relatives, an abundance of flowers and a general atmosphere of gaiety. Smiling, Father Francis accompanied the couple to the church door, where they took leave. Half a minute later he looked into the face of Destiny. Destiny had a small, yellowish face with slit eyes and high cheekbones; blue-black hair; a short, stocky body and short, muscular legs. Destiny smiled and drew a deep breath, rather sharply. It made a low, hissing noise. And Destiny bowed deeply, several times. Destiny was a young man of about thirty-five, of a race or tribe Francis had never seen before in his life. Next to this man stood Captain Jorge Alvarez, grinning broadly. Francis knew him well. He had met him in Goa and at the house of Senhor Pereira. "It's a joy to see you again, Father Francis-allow me to present a friend of mine: Senhor Yajiro. From Japan." Marco Polo already knew about it, although even he never boasted that he had got there. "Chipangu is an Island towards the East in the high seas, fifteen hundred miles distant from the Continent; and a very real island it is. The people are white, civilized and well-favored. They are idolaters, and are dependent on nobody...." Six years had passed since Francis set out from Lisbon. Never in all that time had he met a man with such a thirst for knowledge as this Japanese. Ra the Brahman, had understood him from the start, without an explanation. The supernatural seemed to come naturally to him. Yajiro never tired of asking questions, and behind him hundreds of thousands of faces seemed to loom up, as eager as he for the greatest message the world had ever heard. But the moment came to ask him a few questions, too. " What made you come all this way to see me, Yajiro?" The perpetual smile became just a little strained. "I killed a man, Father." There was a pause. "Why did you kill him, Yajiro?" "He was a samurai-a nobleman, Father. And my wife was beautiful. I killed him." "And-your wife?" "I killed her, of course. But she was only a woman. I was sorry, afterwards, because he was innocent - I found out. His blood was heavy. Also his family pursued me, to avenge his death. I hid. In a monastery. A monastery of my own religion, Father. A Buddhist monastery. But the monks could not help me. Still the blood was heavy on me. Long afterward I met Captain Alvarez. He told me of a God who could forgive bloodshed because his own blood had been shed and he knew. He told me that this God had a great servant, Father Francis. So I came to see Father Francis. A long voyage, very long. I come to Malacca. Father Francis, he has left for islands far away. No one knows when he will come back. Maybe he will not come back at all. Sadly I go home. But the ship will not go home. We run into a typhoon, a terrible, terrible storm. We turn round and round. We turn back. The ship has a will of its own. We go back. When I come here again, there is Father Francis. We have a song in my country:

It is the opposite with you and me, Father. Our ships come from such different harbors and neither of us knew where we would land, yet they rowed towards each other." During a long evening Captain Alvarez had told Francis all he knew about Japan - he had been there twice-yet in a few words Yajiro had told him more than Alvarez ever knew. "She was only a woman." that was what all the peoples and all the nations and all the tribes said, who knew nothing of the Mother of God. Here was a man whose conscience was deeply stricken because he had killed a man‑so deeply that he would travel thousands of miles to find a God who could absolve him from his guilt. Yet it meant nothing to him to have killed his wife. "Christianity, Yajiro, is not just a thing you learn about. It is a thing to be lived." Yajiro nodded eagerly. "It is logical. I believe it. You will teach me, Father?" "I will teach you. And in due course you will be baptized and your guilt will be taken away from you together with all other sins of your life. But you will have to do penance. Is it still dangerous for you, to go back to your country? Will they still be after you for having killed the nobleman?" "It is a long time", said Yajiro. "But there are men who have a long memory." "As a penance-will you go back to your country with me? I shall not ask you to give yourself up, for you will reenter your country as a new man. But I may not be able to shield you, if they come to punish you. Will you come, nevertheless?" Yajiro's eyes sparkled. "You will be the taishi, the Ambassador of God", he said, "and I will be your servant." "It will not be for some time yet, Yajiro. First I must go back to India, to Goa. Will you come with me there?" "I will, Father." On Easter Sunday (1549), after Solemn Mass, he left Goa for Japan. "Let's get on with the writing signs of your language, Yajiro", said Francis. "If the weather changes, we won't be able to do much. What is the next one ‑ah yes, the one underneath, of course. Why can't you Japanese write as we do, from the left to right, instead of from the top to the bottom?" "Why do people in the West not write as we do?" said Yajiro, shaking his head with earnest regret. "It is much more natural. When you describe a man, Father, you describe him from top to bottom, going downwards all the time. Why not in writing, too?" Francis threw back his head, laughing. "You're quite right, really."

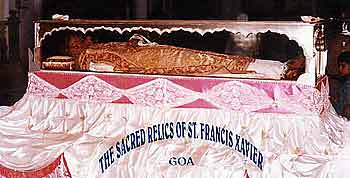

Altar

with the still fairly well incorrupt body of St Francis Xavier,

Book Six WHERE IS Father Francis?" asked Brother Juan Fernândez, fiddling with the joints of a large panel of lacquered wood, "I don't know how this goes together. You'll see, in the end we shall have a cupboard instead of a house." "Father is with Yajiro in the house of Senorita Precious Jade", said Father de Torres. "And if all goes well, she will be called Mary next week. He can't help us with the house building and that's only right. If he were alone, he wouldn't live in a house at all." "And sleep better than we do", Brother Juan nodded. "I caught a streaming cold from the draft . . . . " "And I burned my left foot when I stumbled over a brazier." " . . and if the devil has any sense, he'll copy the Japanese custom of using a wooden block as a pillow for a human head. It's exquisite torture." "To say nothing of sitting on one's crossed legs." "He learned that in India. Father Francis, I mean, not the devil." "He takes to this country like a fish to the water. He even likes that brew they're so proud of. . . " "Chaa, you mean?" "Yes, those crushed little berries, formed like tiny twigs and thrown into hot water. What a fuss they make about it! As if it were the finest Xeres wine." "At least they don't get drunk on it. Pass me the hammer, please." "Here-but be careful-this stuff is so flimsy, you only have to breathe against it and it falls to pieces. They don't get drunk from chaa, but they do from rice vine." "Such wine! I wonder why Father Francis likes it here as much as he does. How can a man trust a country where hell itself is constantly breaking through the mountaintops." Father de Torres laughed. "You might have said the same thing about Italy. Have you never seen Vesuvius? Or Etna? But I think I know why he likes it so much. It's because it reminds him of Navarra." Brother Juan fairly gaped at him. "Japan? Like Navarra? You don't mean that, Father. I can't think of anything more different. In Navarra all is large and upright while here everything is small and dainty, as if it were made for children. The houses, the very trees, the people. . . " "Ah, yes, but consider: Father Francis let me read a letter he had just written home. It was the most enthusiastic letter you can imagine. The Japanese are people with an astonishing sense of honor, they are not wealthy, but poverty is not regarded as a disgrace . . . . " "True." "A nobleman would not dream of marrying a woman of the lower classes, even if she were rich. They are extremely courteous and have much esteem for arms, carrying swords and daggers from the age of fourteen onward. They will not endure insults or mockery." "The points are conceded." "They are moderate eaters-they despise games of chance as just another form of theft-they are monogamous‑" "Right. I can see it now. And he might have added that they are as obstinate as the Navarrese, too. Why, we haven't made more than a handful of converts-a small handful . . . . " "Yes, Father Francis says we must fish with a line here, not with a net. He still hopes he will find the way to the King of Japan and work from the top downward." "He didn't mention that to the Duke, the other day, at the audience?" "The Daimyo, you mean. No. Not yet. But he seemed quite a well-meaning gentleman." "Seemed", said Brother Juan. "That's just it. Seemed. You never really know where you are with them, do you? They're courteous enough, too courteous perhaps, bowing and sucking in their breath‑but I can't help feeling that at heart they despise us." "Of course they do", said Father de Torres cheerfully. "Excellent thing for humility. Ours, I mean. They think we're utter barbarians who have no manners at all. And we do use all the wrong forms of tone and address and so on, you know." "Why do they have so many? To say nothing of their ideographs, instead of a decent alphabet. Ah, well, it's all in the day's work. The lotus flower, sacred to Sakyamuni whom they called the Buddha, no longer opened at dawn, under the first kiss of the sun. But the seven springs in the garden of the Zen monastery went on murmuring, and some of the chrysanthemums were still in flower, great golden, brown and white blooms, larger than a man's head. No obscene carvings, no phallic symbols were worked into the slender beauty of the tile-covered pagoda. This was the Zen monastery in which Yajiro had found refuge, years ago, from his pursuers. Monks were sitting in a triple row on the pagoda steps, in the perfect repose of the lotus posture, their eyes closed or looking into the void. Francis was moved. "What are they meditating on?" he asked in a low voice. Yajiro translated. Old Nin-jitsu, the Abbot, smiled dryly as he answered. "Some are calculating how much money they have received in alms", translated Yajiro. "Some are thinking of the next meal or of a new robe, or of some amusement. None of them is thinking of anything that matters." Francis said nothing. Many a time he had walked through the gardens with the man whose name meant "Heart of Truth" and each time Heart of Truth said something that contradicted what he had said the last time. Once he had spoken of samadhi, as the aim of all meditation, the direct cognition of the nature of the Universe, a kind of sharing of the DivineConsciousness at its periphery‑the Threshold of Happiness, the highest stage of the Eightfold Path of Buddha. And now this . . .

But perhaps the old man was just having his little joke, looking back from the wisdom of his seventy‑odd years to the time when he himself had sat in the triple row, not yet capable of the meditation he was now attempting. "Which period of life", asked Francis, "seems preferable to you-youth or the old age that you have reached?" The old man threw up his brittle hands, as Yajiro translated, and answered with a wistful smile: "Youth, for then the body is strong, and a man can do as he desires." Francis stopped: "What is the best time for sailing from one port to another? When you are on the high sea, exposed to the tempest, or when you are about to reach the haven you elected?" Again the wistful smile. "I understand, I understand what you mean. But I do not know whither I am sailing‑nor do I know how the goal is to be attained." "In Zen Buddhism", Yajiro explained with some difficulty, "there is no place for anything beyond birth and death. It is different, somewhat, with Shingon‑Buddhism and again with Shin and with Soto and Shinto. Not all are like these here. Some are better, some are worse." The Shin monks married and many of the others indulged in unnatural vices both among themselves and with their pupils, although others lived austere and ascetic lives, striving earnestly for the "threshold" of the highest Path. Yet none of them knew that the final goal of man was not a threshold, but the entering into the sanctuary and the life in it, and that by living in it they could still be themselves, instead of being absorbed by the "All"; none of them knew that Christ had opened heaven to man by descending into time and space and matter and dying for mankind on the Cross. They were living in a twilight sphere, particles of the All, little drops of water striving dimly for absorption in the ocean - and when a drop of water was absorbed by the ocean, it certainly was the end of the drop as such. And in a flash Francis understood that Buddhism could be anything. That by itself it could not satisfy the urge in man and would be mingled either with superstition or‑with the truth of God. It could become, it could develop into anything. It was not absurd that this old man was called Heart of Truth. There was in that name a longing, of which the old man was no longer aware .... "Maria," said Francis, pouring water three times over the girl's glossy black hair, "ego to baptizo in nomine Patris‑et Filü‑et Spiritus Sancti .... "

The

left hand of the Saint. His right hand is kept in the Church of the Gesu in Rome. The tiny figure in the flowery black kimono stood immobile, eyes downcast, hands folded. But the smile on the beautifully curved lips was no longer the ready smile of habitual courtesy, offered to everyone and shielding the true emotions. This was a happy snüle. For the girl who had been Precious jade and who now was Maria stood at the threshold by the merits of Christ and the strength of her own will. Long years were ahead of her before she would reach the sanctuary. No flash of sudden enlightenment told her that twelve years hence she would be a member of a Christian community of two hundred souls - or that in another twenty years she would be the only Christian soul in Kagoshima, all the others either dead or fallen by the wayside. The only Christian, mocked, jeered at, persecuted for her faith and still clinging to it as she would cling to the simple rosary Father Francis gave her at her baptism, wearing it round her neck in the open streets, resisting the anger of the Buddhist bonzes and the entreaties of her own relatives that she invoke Buddha Amida and the kamis, the house gods. Thirty-five years hence, Brother Damian, a Japanese Jesuit, would find her and report about her to the Superior of the Jesuits in Japan who sent for her and transplanted her to Nagasaki, where there was a flourishing Christian community and where she ended her days in peace, and was buried with Father Francis' rosary round her neck. Two weeks later Francis said farewell to Yajiro. "We are forbidden to go on working. We must go. But instead of fleeing, we shall march forward till we reach the capital and the King. It is as I thought: only by winning over the King of this country can we win altogether. Do you feel that you are still in danger here? If you do, I could take you with me and leave Brother Juan Fernândez here instead. By now he can speak Japanese quite well-I wish I had his gift for languages." "Brother Juan will be able to serve as an interpreter", said Yajiro. "This is my country. I will stay here, Father, and look after those who have accepted the Faith." "You did not answer my question about the danger, Yajiro." "All of us are in danger, Father", said the Japanese simply. "And yours perhaps is greater than mine. God alone knows." Father Francis Xavier and Brother Juan Fernândez were on their way to the King. They had left Father de Tomes in Hirado, where Daimyo Matsura Takanuba continued to be friendly. They knew very little about the King. People would not talk much about him. Was it because he was regarded as a kind of sacred figure? Some at least seemed to think of him as that. He was the "Son of Heaven", the direct descendant of Amaterasu Omikami, the Sun goddess. But Daimyo Shimatsu of Kagoshima never spoke of him, and when asked directly, slipped off to a different theme. And he acted as if there was no one to whom he owed an account of his stewardship. Daimyo Matsura Takanuba told them the way to o, if they wished to find the Son of Heaven, but noting more than that. The King was a mysterious figure. As the head of Shinto he was a religious figure. If it was possible to win him for Christ, if he would come out of his remoteness and declare the new religion . . . Kyoto was his residence. Kyoto, a city of many hundreds of thousand houses, they said. There he reigned in incredible splendor, aloof and mystical, the ruler of sixty-six kingdoms on all the islands of Nippon. They had to spend the nights under a roof of some sort for it was now too cold to sleep in the open. But the inns were very dirty and the food almost uneatable. For many days they lived on nothing but rice. Only in a Zen monastery they found warmth and good food. But they left without spending a night there, when they saw what was going on between the monks. Francisthrough the medium of Brother Juan told them what he thought of them. They seemed to take it as a huge joke. When they left it was beginning to snow. Snow. They crossed by sea from Moji to Shimonoseki, ragged beggars, stared at and despised by the other passengers of the little vessel. It was good to rest one's feet for a wile. It was not for long. Snow again. Here on the island of Honshu people were different. Perhaps it was because foreigners never came here at all. Even the children were nasty and suspicious, pelting them with stones or filth, and shouting insults. There was little left now of the daintiness and the charm of the Japanese landscape. It lay under its huge white blanket in a state of rigor mortis. "Now I understand why white is the color of mourning in this country", said Brother Juan Fernandez grimly. There was no answer. Father Francis was walking as if he were in a dream, eyes downcast, arms folded. He was tired, of course. But was it only that? "Do you think we shall find a place to spend the night, Father?" Again there was no answer. Brother Juan Fernândez fell back a little. It seemed to him that Father Francis had grown, grown to such size that it was not right and meet to walk beside him. He was walking across the blanket of the tremendous corpse that was Japan. He was walking barefoot and always there was a trace of red where his feet had touched the snow. Blood. He was sowing his blood into the soil of Japan. Would it bring the corpse to life? Suddenly Francis stopped in his tracks. He bent down. When Brother Juan reached him he saw a tiny, emaciated body in his arms, a newly born child, a girl, still alive but beyond all hope of recovery. Here, too, just as in India . . . Francis gave her to Brother Juan to hold. With the warmth of his breath he melted a little snow, to baptize her. The baby died half an hour later and they buried the tiny body under a maple tree and prayed the prayers for the dead. Then they went on. In the great wooden city of Yamaguchi the Daimyo Ouchi Yoshitaka listened to the ragged strangers, but would not give them permission to preach or baptize. In the streets they met with open contempt and once more the urchins ran after them, throwing stones and filth. "Chikushômé! Kum!" "What do they call us?" asked Francis calmly. "Beasts and dung", replied Brother Juan. They followed the coastline to Sakai. But from here on they knew they would not be able to travel alone, if they were to reach their destination. It was the most lawless and dangerous part of the whole country. A samurai, on his way to Kyoto, gave them permission to travel with his servants. The samurai was on horseback. His servants had to be quick. But this was the last stage of the journey. A few more days and they would at long last meet the King. Francis forgot his weariness. The nearer they came to Kyoto, the more cheerful he became. He was wearing a Siamese cap somebody had given him back in Hirado and now he gave it a rakish angle. Brother Juan laughed. The samurai's servants eyed the strange pair, half-bewildered, half-amused. Some said that they were from Siam, the Land of the Gods. Others knew that they were barbarians from the South - from India and probably quite mad. As it was always a good thing to humor a madman, one of the servants gave Francis an apple. Francis promptly began to play with it as a child plays with a new ball. He threw it into the air, ran forward and caught it, threw it up again, caught it again… Now there was no doubt that he was mad hoping about on his swollen, bleeding feet and laughing and singing. The scarecrow that was the Papal Nuncio for the East and Far East and Ambassador-Extraordinary of the King of Portugal and his scarecrow companion stood before the Imperial palace of Kyoto. It was an enormous, sprawling, ramshackle building, a maze of buildings, rather, with gardens and parks, surrounded by a bamboo stockade. If it had not been for a few curious faces, peering at them from large holes in the stockade the whole thing would have given the impression of being utterly deserted. It was not yet in ruins, but it looked as if it soon would be.

The head of St Francis Xavier A small door opened, creaking, and a soldier stepped out. Perhaps a sentinel? He wore a lacquered helmet, and a shabby breastplate and carried a rusty spear. He walked up to them. "Who are you? What are you doing here?" Brother Juan explained that they had come from afar to see the King. "The Tenno?" asked the soldier. "The O? The Dairi? Why should he see you?" Brother Juan explained that they were special envoys from a country called Portugal. The soldier walked all around them and grinned. "It must be a strange country", he said. "Where are your presents?" Brother Juan was prepared for that question. They had not brought their presents with them. They would fetch them after the audience. The soldier laughed contemptuously. "You come without presents and you expect to be received? One would think you had come from China that you imagine all doors must open to you as soon as you appear." Francis listened carefully to Brother Juan's translation. "China?" he asked. "Why China?" Brother Juan passed on the question. Again the soldier laughed. "It is the country of the great Dragon, the country of the middle of the earth. Even the Son of Heaven speaks of him who rules China as of his elder brother. All good things come from China. Who are you that you do not know what a child knows?" "Tell him", said Francis, "even China cannot bring the King as much good as we are bringing." The soldier raised his eyebrows. "You have money with you, maybe? If you have five hundred silver tael, the Son of Heaven may consent to sell you a poem he copied. If you have a thousand, he will certainly sell you a poem, perhaps even one he made himself. You have no money? Baka, fool, you are wasting my time. Go back where you came from." He turned away and sauntered to the bamboo door. "I understand now", said Brother Juan. "The King has lost his authority. Kyoto is a forgotten city. Did you see how many houses were in ruins? I'll wager there are no more than fifty people in that palace. The poor man is selling poems. And for this we have come all that way . . . . " Francis smiled. "It would have been enough to come all that way to baptize the child we found dying in the snow. But there is more, Juan. Perhaps that soldier is quite right . . . . " "What do you mean?" "China", said Francis. It sounded like an invocation. All good things came from China. The ruler of China was the elder brother of the Son of Heaven. The ruler of China was a real ruler, a real king, whose subjects obeyed him implicitly. If the ruler of Japan became a Christian, it would not inspire his subjects to emulate him. Not he, but the Daimyos really ruled the country. But if the King of China became a Christian, his subjects would follow his example. And then Christianity would come from China to Japan, from China whence all good things came .... It was worthwhile to march for weeks and months, just to find and baptize a dying Japanese child. But only if China became Christian first, would the whole of Japan adopt the new religion, too. Surely that was what Father Ignatius would think. Time and again he had heard the Japanese speak of China in a tone of awe and reverence. Yet it was a simple soldier who pointed out the way to him. China. After a few days of rest they left the magnificent squalor that was Kyoto. The way back to Hirado was even more difficult, with the winter at its height. Plowing his way through the snowdrifts, Francis suddenly smiled. "What are you thinking of, Father?" asked Brother Juan. "Of the first church in Kyoto", said Francis. "It will be called the Church of the Assumption of Our Lady." Brother Juan gasped. Brother Juan gasped again in Hirado, when Francis declared that he would go back to Yamaguchi once more, before leaving Japan. "But that's where we were treated worse than anywhere else!" "And that may well happen again", Francis nodded. "But this time we shall have a different approach. They like presents and trappings. They shall have both." He had made friends with a number of Portuguese merchants, and they helped him to organize a caravan with presents that even the richest Daimyo would have to respect: an arquebus, three crystal vases, a bale of brocade, a Portuguese dress, mirrors for the ladies, several pairs of spectacles for restoring the sight of the short-sighted, a manicordia playing seventy different notes and above all a chiming clock. Both Francis and Juan had new cassocks and surplices and Francis a stole of green velvet. They did not ask for an audience. They just sent the presents. Daimyo Ouchi Yoshitaka was vastly impressed and sent them a large sum of money. Francis promptly sent it back. "It is not money that we want, but your permission to preach and to baptize." It was granted. Moreover, the Daimyo put a large deserted monastery at their disposal, "In order to develop the law of Buddha." Francis winced when he heard it, but he understood: it was the Daimyo's way of covering himself against the bonzes. Now the work started in earnest. Once again Yamaguchi showed itself at its worst. Brother Juan's Japanese was still far from classical and the crowd jeered at him wherever he spoke. "Deus... " ejaculated Francis. "Dal-uso-big lie", howled the street urchins gleefully. A brutal looking man stepped forward and spat straight into Brother Juan's face. A sudden hush went over the crowd. This was a deadly offense. Death was hovering over the offender. The crowd waited. "Jesus cured the leper", went on Brother Juan, "and he performed many more miracles. But in their hatred, they had him arrested and when he was in their power, one man spat into his face. Later they nailed him to a cross. But he did not curse them. He prayed: `Father, forgive them for they do not know what they do.' Then he died so that by his sacrifice man should be reconciled with God." A crowd of common people did not observe the rigid self-control of the samurai. There were tears in many eyes now. Another man stepped forward, with a queerly shuffling gait. He was bald and blind in one eye. Under a tiny button of a nose his mouth was as broad as a frog's. His ears were enormous. He had a biwa, a kind of mandolin, slung over his shoulder. "I make people laugh", he said in a loud voice. "But you make them cry. You are my elder brother." No one laughed. Juan saw that the man had tears in his eyes too. "Men are born to be brothers", he said gently. "Tell me," said the queer-looking man, "is it true that you have come from very, very far?" Brother Juan tried to explain the distance between Lisbon and Yamaguchi and the people all around them made little noises of admiration. "And you traveled all that way", asked the man, "to tell us about your God? For no other reason?" "For no other reason." "Brother," said the man, "at long last I have seen men who live what they believe and who mean what they say. Such men must either be fools, like I am, or... " " . . . Christians", said Brother Juan. "You are living at the monastery on the Hill of the Little Pheasants . . . . " "We are." "Will I be allowed to come and see you there? I have many questions to ask, if your forbearance and patience will permit." "You will be very welcome‑and so will everybody else”. When they came home they found a man waiting for them. He was about forty and his dress, like the sword and dagger in his belt, showed that he was a samurai. "I was very much opposed to your coming here", he said after a courteous greeting. "But I was present today and saw and listened. I thought there could be, to such offense, only one of two reactions: that of the coward or that of the man of honor. I was wrong. There is a third reaction. It has nothing to do with cowardice, for cowardice will blanch and tremble. And it has nothing to do with honor, because the Fujiyama is not dishonored when the droppings of a dog fall on one of its slopes. Yet I know that no samurai would have been able to keep self‑control as you did. Therefore I have come to find out more about the things you are teaching."

Walking

the burning sands of South India Six months later Father Cosmas de Torres came from Hirado to take over a community of five hundred Christians. "There are two Portuguese ships in the port of Hiji", he told Francis. "I told them to wait for you." Francis nodded. He introduced Father de Tomes to his flock. "He and Brother Juan will be your guardians. But remember to put your trust in God." He embraced Brother Juan. But his final word was for a lay brother, a Japanese with a ridiculous face, blind in one eye, with a button of a nose, a mouth as large as a frog's and enormous ears. Nowhere else in Japan had he found a man of such gifts as this wandering singer and juggler. "You can make people laugh and cry now, Brother Laurence", he said. "Now go and teach the people as I have taught you." "I will, Father", said the man simply. "Just tell me where you wish me to go first." "To Kyoto", said Francis. They were waiting for him in the port of Hiji. The two Portuguese ships ran up flags and fired their guns. More important were two letters from Father General Ignatius. In the first Father Ignatius called him back to Europe. The second canceled that order and made him Provincial for all the districts east of the Cape of Good Hope. That meant that he would have to go to Goa. He sailed in September. To his baggage was added one book. He read in it every day. It was a book about the Chinese language and its way of writing. |