![]()

![]()

|

Newsletter of the District of Asia May - September 2007 Japanese

Christian Art In the Jesuit Century

The demand for Sacred Art It is certain that St. Francis Xavier and his party, arriving by junk in Kagoshima, Japan, in 1549 brought with them articles to use in their mission and to exchange as presents, and that among these were pictures of Christ and the Virgin Mary. No sacred pictures had as yet been produced in Goa, however, and because Xavier, the first missionary to visit Japan, knew little of conditions there, the number he brought was limited. Soon after his arrival the mother of Shimazu Takahisa, daimyo of Kagoshima, asked him for a picture. Reporting the incident later, he said, “We had no means of making a copy of the picture in this country, and there was no way to accede to the lady’s request.” The Jesuit missionaries who followed him (by 1581, twenty-two years after the introduction of Christianity, there were in Japan seventy-five missionaries) also brought a number of pictures. Considering those priests who returned to India after a number of years and those who died in Japan, the total must have exceeded eighty, so that the number of works they brought to Japan can by no means have been small. Moreover, with each year after the introduction of the faith, the strength of evangelistic activity increased in Hizen, Bungo, the Kinki district, and other areas, and the number of converts increased rapidly until in 1581 it reached 150,000, necessitating the maintenance of 200 churches.

A

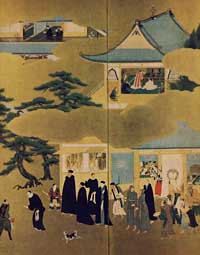

17th c. Namban Screen depicting the arriving of the Portuguese.

Japanese artists had sometimes been set to copying religious art brought over by the missionaries, and many of the resulting works were said to be extremely well executed, well enough to be sent with the embassy of the Kyushu daimyos for presentation to the Spanish court. Since the majority appear to have been made in Kyoto or Sakai, it is likely that it was the artists of the Kano and other important schools who received the commissions. These works, however, were somehow unsatisfying as works of church art, and their numbers were limited. Finally the missionaries in Japan petitioned the Jesuit Curia in Rome to provide them with religious art, but since it was seven or eight years from the dispatch of this order until delivery, the immediate problem remained unalleviated. The requests to Rome for religious pictures during this period were repeated several times, and the need in Japan for 50,000 works, given in the Society’s report of 1584, can have been no exaggeration. Yet it was quite impossible for Rome to satisfy these requests. For we are told that when a certain missionary bound for Japan was entrusted with one thousand paintings, his artworks were preempted in India, Malacca, and other points en route, so that virtually none were delivered to Japan. Religious prints from copper printing plates were also in great demand for the faithful, and in the Jesuits’ reports and correspondence of 1584 and 1587 strong requests are made that some be sent. This in itself indicates that there were then few copperplate prints in Japan. Art, Propagation and Education The requests of the Jesuits in Japan were not confined to religious art. They early became aware that in order to extend the Christian religion it was absolutely essential for them to provide convincing and irrefutable comparisons between Europe and Japan in regard to the Church’s authority, the power and dignity of temporal princes, and the prosperity and affluence of the cities. It was to this purpose that Alessandro Valignano set himself. The Jesuits’ visitor and their highest official in the Far East, Valignano began his tour in Japan in July 1579, and after a stay of nearly three years, departed with the Christian daimyos’ embassy, going with them as far as Goa. No sooner had he arrived there, than he took numerous occasions to direct—both in letters to his superior, which he entrusted to the envoys, and in his instruction to the missionaries who accompanied the group— that the young envoys be shown how mighty the Church, the princes, and the cities of Europe actually were. He also expressed a corresponding desire for pictures to be used to educate the Japanese. The Jesuit report of 1587 requested illustrations of the city of Rome and of pontifical masses to be used to instruct the faithful in the majesty of the Catholic Church, and stated his desire to obtain pictures of European knights and warfare, these being very popular among the Japanese. Obviously these desires were not to be easily met. In this connection Valignano had begun in 1579 a thorough inspection of conditions relating to the propagation of the faith, and subsequently solicited the missionaries’ opinions of its future. Some of the policies he evolved to rectify deficiencies in the program are given briefly here. One of these was to establish preparatory schools for Japanese aspirants to religious vocations, those who would be compatible intellectually and socially with the growing population of converts. Such institutions were established at Azuchi, the headquarters of Oda Nobunaga, predecessor of Hideyoshi; at Funai and Usuki in Bongo Province, the domain of Otomo Yoshishige, who was the most important supporter of the Society; and at Arima, Hizen, in the domain of Arima Harunobu, a fervent Christian and admirer of Valignano. Another policy was that the Society of Jesus in Japan become self-sufficient in producing literature by doing their own editing and printing. This was because it would require inordinate, labor if each missionary or student handcopied the school texts and the many works required by the faithful, while to obtain them from Europe would not only be extravagantly expensive and difficult, but would fail to provide works tailored to the needs of the Japanese. As part of this program a catechism was translated from Latin, carried by the young envoys to Europe, and published in romanized Japanese at Lisbon in 1586.

Whatever Valignano may have done during his stay in Japan for correcting the scarcity of art objects is not mentioned in the Society’s reports. It may well be that the requests to the Curia for getting artworks were at his instigation and that he also planned to give, in the schools at Azuchi, Funai, Usuki, and Arima, instructions to the Japanese in art and crafts as well as in the more conventional subjects, thereby producing a cadre of experts. But since there was no one among the missionaries with sufficient talent to impart such techniques, we are left in doubt about whether these plans ever came to fruition. Valignano left Japan the first time in February 1582, and during his stay in Macao, which lasted from March until the end of the year, he made the acquaintance of the young Italian painter and Jesuit Giovanni Niccolo, who was being sent by the Jesuit Curia to Japan. Niccolo arrived in Macao from India in early August of that year and remained there until late the following spring. His presence there coincided with that of Pedro Gomez (1535-1600), later to become a vice-provincial, and of Francisco Pasio. Valignano called all of them for discussions on various aspects of the evangelization of Japan. It is likely that the perennial problem of art and artworks came up, and possible that Valignano directed them in some related policy. Niccolo, with his two superiors, Gomez and Pasio, reached Nagasaki in the summer of 1583. It seems that for some years after his arrival, he was not blessed with good health and was unable to devote himself fully to painting. Available knowledge suggests that in Macao he painted, in addition to his Savior, a map of Italy in oils. The many works he did in Japan include a Christ painted for the faithful of Nagasaki and another for those of Arima, both dated 1583, and in 1584 a figure of Christ for a newly built church in Arima. Also in 1584 he painted a Mary in oils on heavy panels for the church in Usuki in the fief of Otomo Yoshishige, but this was destroyed when the Shimazu armies invaded Bungo Province in that year. He was commissioned by the vice-provincial Gaspar Coelho to paint a large and splendid representation of the Savior for dispatch to Macao, and he also turned his hand to producing a number of copperplates, and even an oil of Stephen the Apostle. But the unfortunate fact is that not one of these has come down to us today. Niccolo died in Macao in 1626. A letter written from there that year by one Palmeiro, a missionary, tells us that he stood head and shoulders above the other missionaries in Japan and China, “possessing great gentleness and probity, having a special talent for mathematics, painting, and clock making, instructing students in painting, and providing religious pictures for the churches.” This indicates that he was a man of many parts, exemplifying the artist of Renaissance Italy. And it is probable that with his recovery of good health, about the time of Hideyoshi’s proclamation expelling the missionaries, he taught painting and woodblock printing to the Japanese students at Hachirao, in Arima. If it is true that he received instructions from Valignano at Macao in 1582, they no doubt were in reference to the teaching of students of painting. Whether he did or not, nothing whatever is known about the Jesuits’ activities in art instruction until 1590, when Valignano returned to Japan armed with a diplomatic commission from the viceroy of India. In August he assembled the missionaries for a meeting at the Jesuit theological college at Katsusa, on the southern end of the Shimabara peninsula. At that meeting it was decided to print textbooks using the presses and types that the mission had brought from Europe, and, with an eye to the future, to cast Japanese types as well; printing was begun forthwith, in October. I mentioned earlier that Valignano sent a catechism manuscript in romanized Japanese to Lisbon with the Christian daimyos’ embassy, where it was printed in 1586 for use in the Jesuit schools in Japan. And at Macao, on his way back from India, he had printed, for the same purpose, Bonifacio’s Education of Children in 1588, and a record of the embassy in question-and-answer form in 1590; both were in Latin. This work was accomplished by having members of the mission in Lisbon trained in the casting of type and the techniques of printing, and by bringing back type and presses.

Even before this, at the end of 1588, there were in the preparatory school at Hachirao some 75 Japanese students, and by 1596 the number had grown to 112, so that the problem of supplying texts was not an easy one. With the return of the mission, the means for overcoming the difficulty came to hand. Thanks to Valignano’s careful planning, in 1591 the first work ever printed with movable metal type in Japan, Sanctos no Go Saguio (Acts of the Saints), was published at the college in Katsusa, and from then on, works were published almost every year. It is likely that provision had been made for the production of works of art, as it had for the printing of texts, but no mention is made of this in the Jesuits’ reports. Quite probably Niccolo and the returning members of the Christian daimyos’ envoys brought into Japan materials for Western-style painting and the chisels and other tools used in the working of copperplates; but even if they did, the amount must have been insufficient, requiring the printers to use domestically produced materials. At the October 1590 conference in the college at Katsusa, where it was decided to undertake the printing of textbooks, consideration was probably given to the production of works of art, and steps were soon taken to begin instructing students. And while it seems obvious that the training was begun with the students copying religious works, it is unlikely that such nonreligious themes as cityscapes and portraits were neglected. The Beginning of Western-Style Painting in Japan No materials exist that would enable us to fix the precise date when the Japanese study of Western painting began, but a clue is provided by the screen painting Four Great Cities of the West belonging to the Kobe Museum of Namban Art. As we have seen, Valignano’s embassy from the viceroy of India stayed for about two months in the Japanese port of Morotsu on its way to Kyoto around the beginning of 1591. And it is reported that during the talks on conditions in Europe that the members of the Kyushu daimyos’ embassy gave to the many lords who visited them, they displayed many objects, among which was an exquisitely executed work showing Rome and other cities. One cannot state with certainty that the Kobe Museum painting is the one they displayed; they may have had a reduced-scale copy made for easier carrying. But any such paintings would have been produced at the section of the Jesuit school devoted to Western painting either by Niccolo, working alone or assisted by his Japanese students. If it was done at the school, it must have been completed by early December, when Valignano’s party set out from Nagasaki. It follows then that the copying of Western-style painting had begun by the fall of 1590. And since it had long been the desire of the Jesuits to show to the Japanese people works depicting the city of Rome, it is safe to say that they proceeded with copying as soon as humanly possible after the return from Europe of the envoys. There is, then, virtual certainty that Niccolo started teaching Western painting along with copperplate engraving. In that part of the Jesuit report of 1592 dealing with the school at Hachirao in Arima’s domain, we find that, “among the students are some who, in accordance with their own interests, practice other disciplines (not on the standard curriculum). For example, some study painting, while others learn painting or the engraving of copperplates. Their technique is very fine, for they have the most excellent and rare skill and one can only be amazed to see the ease with which they comprehend. If your Paternity (the Jesuit General) were to see the things produced by these inexperienced youths, you could not but be pleased.” And that both paintings and copperplate prints began from the copying of originals brought back by the Christian daimyos’ envoys is made clear in the report of 1593. Since this is a most important passage, I would like to quote it here at length.

“The fact that a number of the students at the Hachirao School are painting pictures and engraving metal plates is greatly to the advantage of the Church. Eight of them are painting with Japanese colors, [eight] others in oils, and five are engraving copperplates. They are, without exception, making great progress and astonishing us greatly. For there are among them students who have made copies of the best works brought by the Japanese princes from Rome, and these copies are so nearly perfect in both color and shading as to be almost like the originals. Many of the fathers and brothers associated with them cannot tell which were made by the students and which brought from Rome, and although this may be thought an exaggeration, there are even some who insist that the work produced by the Japanese was brought from Rome.... And some of the Portuguese, seeing the works, and not knowing them to be made in Japan, have said that they can only have been made in Rome. If we are thus blessed by Divine Providence, we shall have people who hereafter will fill our many churches with fine paintings, making glad the faithful lords and gentlemen. Engravers of copperplates apply themselves diligently at their place of work. For in making engravings in perfect likeness of those brought from Rome and printing from them, they can give great joy and satisfaction to the faithful. The pious desire of the faithful to have pictures in their own houses, which was so long unattainable, is now in the process of being achieved.” This report shows that the Japanese students were intent on making faithful copies of Western works, and had not added any peculiarly Japanese flavor. This was not only because they were in the early stages of their studies but also because the Church wished that as few changes as possible be made in the originals. They did, however, take pains, both in the making of paintings and copperplates, to develop a method of copying which provided some changes in posture or in the number of auxiliary figures, so as not to be confined to stereotyped reproduction of a small number of originals. From The Namban Art of Japan, by Yoshitomo Okamoto, pp. 96-113 32

|