This

issue of the Angelus English-Language edition of

SISINONO is the second installment of the

second half of a double study regarding the “state of necessity”

invoked by Archbishop Lefebvre to justify his consecration

of four bishops on June 30, 1988. In our issues of SISINONO

of July

and September

of 1999, we discussed the theological

aspects. Starting with the November

1999 we are discussing the canonical

aspects. These remarks are for those who admit the existence

of an extraordinary crisis in the Catholic Church but do

not know how to justify the extraordinary action of Archbishop

Lefebvre on June 30, 1988 when lacking permission from Pope

John Paul II, he transmitted the power of episcopal orders

to members of the Fraternity founded by him.

CANONICAL

STUDY – PART 2

II.

A CONTESTED EXCOMMUNICATION

A.

The Facts and Some Solid Points

1. The

Facts

In

his "Thesis for a Licentiate" in Canon Law which

was argued and approved with the highest grade (July, 1995)

at the Pontifical Gregorian University, Rev. Fr. Gerard

Murray, an American priest who has no connection with the

Society of Saint Pius X, held that the excommunication latae

sententiae, declared at the time against Archbishop

Lefebvre, Bishop de Castro Mayer, and the four bishops consecrated

by Archbishop Lefebvre without pontifical mandate, is not

valid according to strict canonical law , nor is the connected

accusation of schism valid in the formal sense. As of yet,

his thesis for the licentiate has not been published, but

a summary of it and an interview with its author is available

in the American magazine, The Latin Mass.1

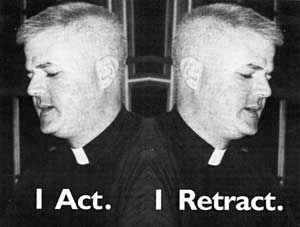

Two

facts must be mentioned: 1) Fr. Murray

made a partial retraction of his own thesis (Summer, 1996);

and 2) the Pontifical Council for the Interpretation

of Legislative Texts has published its opinion that the

excommunications were justified. Though the council is entrusted

with interpreting the laws of the Church, it is not a font

of law itself and its opinion, in any case, was anonymous.

The "Murray Thesis" is not even considered for,

it said, "It is impossible to evaluate the Murray Thesis

because it has not been published and the two articles [of

the magazine- Ed.] which appeared about it are confused."2

Could

it be that the thesis is contrary to the public policy of

the Gregorian University? Since it has never been made available

in the original, we are forced to discuss the arguments

based on what appears in the magazine articles, despite

the fact that the pontifical council asserts they are "confused."

Without a doubt, a scholarly analysis would have considered

the thesis of Fr. Murray, but the council's denial has silenced

its viewpoint. On the other hand, Fr. Murray published his

retraction one year before the appearance

of the opinion attributed to the Pontifical Council. Why

on earth would this council have to say anything regarding

arguments already formally, even if partially, retracted

by their author?! - Retracted, by the way, even before a

wider public with authoritative knowledge had been able

to read it.

2. Solid

Points

1.

Whatever may be the changes of opinion of Fr. Murray

about his own work and the motives for not publishing

it, the fact remains that the thesis had been approved

with the highest grade by the professors of the Gregorian

University, conferring on this work exceptional value.

This approval must be held in due regard.3

2.

The extract of the "Murray Thesis" which

appeared in The Latin Mass is sufficient to understand,

namely, that the American priest, with Code of Canon

Law in hand, denies - or if you prefer, places into

doubt - the validity of the excommunication ipso iure

applied to Archbishop Lefebvre because he acted in a state

of necessity without bringing into being any schism. According

to Fr. Murray, it is necessary to recognize that, on the

basis of the canon law in force, the excommunication of

Archbishop Lefebvre is substantially invalid and the schism

does not exist. It is thesis undoubtedly courageous and

above all founded on law, even if we may not agree with

the hypothesis of Fr. Murray that Archbishop Lefebvre

was able to have been mistaken in good faith about the

existence of the state of necessity which authorized him

to proceed with the consecrations. In any case, the partial

retraction of Fr. Murray concerns only the admissibility

of the state of necessity, not the existence of a schism

in the formal sense.

B. Precedents

Fr.

Murray is not the first to maintain the invalidity of the

unjust excommunication declared against Archbishop Lefebvre

and the non-existence of the so-called "schism"

imputed to him. We recall the reader to the canonical study

of the German canonist, Rev. Fr. Rudolf Kaschewski, which

appeared in Is Tradition Excommunicated? [available

from Angelus Press. Price: $7.95], on the aspect of the

episcopal consecrations without papal permission.4

This study, published shortly before the episcopal consecration

of Archbishop Lefebvre and by an author independent of the

Society of Saint Pius X, demonstrates unequivocally that,

on the basis of the 1983 Code of Canon Law, the episcopal

consecration without pontifical mandate cannot be punished

with excommunication. In fact, the author writes at the

conclusion of his essay:

Therefore,

the widely spread opinion that the consecration of one

or several bishops without papal mandate would cause an

automatic excommunication and would lead to schism is

false. Due to the very terms of the law itself, an excommunication

for the aforementioned case could not be applied, neither

automatically nor by sentence of a judge.5

The

article appearing in the original Italian SISINONO

of July 1988 (XIV) 13, titled "Neither Schismatics

nor Excommunicated" [reprinted in Is Tradition Excommunicated?,

pp.1-39] demonstrates how, in the case of the episcopal

consecrations for the Society of Saint Pius X, all five

of the conditions required for taking advantage of the law

corresponding to the state of necessity had been realized.

They are namely: 1) the existence of the state

of necessity; 2) attempts having been

made to remedy it with ordinary means; 3)

the "extraordinary" action not being based

on an act intrinsically evil nor harmful to neighbor; 4)

having remained within the limits of the requirements actually

imposed by the state of necessity; and 5)

never having put into question the power of the competent

authority, the consent of which it would have been able

to presume in all legitimacy in normal circumstances.6

Though

the Vatican officially denies its existence, a bleak picture

of the real state of necessity in the present-day Catholic

Church was painted by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger in his speech

to the Chilean Episcopal Conference (July 13, 1988) on the

latest developments of the "Lefebvre case." The

discourse, printed by the weekly Il Sabato of July

30, 1988, was reproduced by the Italian edition of SISINONO,

November 15, 1988, (XIV) 17, with the title, "Cardinal

Ratzinger Demonstrates the State of Necessity in the Church."

The

same Cardinal Ratzinger states in his discourse that Rome

is not carrying out its necessary and indispensable functions

and the bishops do not make use of or have made it utterly

impossible to make use of that power which by divine right

they possess in the Church for the eternal salvation of

souls. It is the same Cardinal Ratzinger documenting that

state and that law of necessity, to whom His Excellency

Msgr. Lefebvre made his appeal when on June 30 he took

advantage of a juridical competence outside of the ordinary.7

The

passage of the speech of the Cardinal to which reference

is made is the following:

Criticism

for the choices of the post-Conciliar period is not tolerated:

but, where the ancient rules, or the great truths of the

faith - for example the bodily virginity of Mary, the

divinity of Jesus, the immortality of the soul, etc.

- are at stake, we do not react at all or we do it with

extreme moderation. I myself was able to see, when I was

a professor, how the same bishop who before the Council

had expelled an irreproachable professor for his somewhat

uncouth speaking, was not able to remove, after the Council,

a teacher who was openly denying some fundamental truth

of the Faith. All this drives many people to wonder whether

the Church of today is really that of yesterday, or if

it has been changed into another without informing them…."8

We

have to help us the essay "Neither Schismatics nor

Excommunicated," the work of Fr. Kaschewski, Dr. Georg

May's "The Disposition of Law in Case of Necessity

Within the Church," [see both in Is Tradition Excomunicated?,

pp.1-39; 111-113], the discourse of Cardinal Ratzinger,

together with an article on the correct idea of tradition

and with three appendices have finally been combined into

one volume entitled Is Tradition Excommunicated? [available

from Angelus Press, Price: $7.95]. Nor can we forget the

careful study of Fr. Gerard Mura, Les sacres episcopaux

de 1988. Etude theologique, which we mention

in the competent synthesis published in French by the magazine

Sel de la Terre, in four issues, in 1993 and 1994.9The

salient contribution of this study, which is built on a

prevalently theological plane, is on the thesis that "the

pontifical prohibition for the celebration of the consecrations

ought to be maintained as null and not having happened"

because "contrary to the common good of the Church,

a factor for the defense of the faith; defense of the faith

which, aware of the state of necessity in which the Church

exists, was demanding the consecrations done by Archbishop

Lefebvre.

The

book of the American Catholic lawyer, Charles P. Nemeth,

The Case of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre: Trial by Canon

Law [Angelus Press, Kansas City, 1994. Price: $9.95],

must be mentioned. It presents a strictly juridical analysis

which denies the validity of the excommunication and of

the accusation of schism, reaching the same conclusion as

Fr. Kaschewski.10

We

have wished to mention these precedents also in order to

draw attention to the fact that Fr. Murray concludes to

a point substantially similar to Fr. Kaschewski's. It can

be said, in fact, that Fr. Murray applies them to a concrete

case. In our mind this shows that the tone of the norms

of the Code of Canon Law is clear enough to have

de facto permitted the establishment of opinions

that are "on the same beam." As laid down by strict

law, the excommunication could not be declared nor could

the censured act be maintained as schismatic.

III.

JURIDICAL TERMS CONCERNING THE QUESTION

A.

Excommunication

Let

us consider the strictly juridical terms concerning the

question so the reader is able to get the clearest picture

possible.

Archbishop

Lefebvre has been condemned for having consecrated four

bishops without papal mandate. On this argument let us follow

the commentary of Fr. Kaschewski:

1.

Episcopal consecration occupies the highest place in the

hierarchy of consecrations:…The bishop enjoys two powers:

I) the power of Order (in which is included the power

to consecrate priests and bishops); and 2) the power of

Jurisdiction, which he cannot exercise if he is not in

possession of a diocese. The episcopal power is a power

of divine right which confers on the bishop a proper authority

and assures him of a juridical-constitutional autonomy

which not even the pope can suppress or modify.11

This

autonomy which the bishop enjoys depends on the nature of

his power, which springs directly from Our Lord because

bishops are the successors of the Apostles and hence enjoy

that power which was conferred personally by Christ.

The

autonomy of the episcopal power, nevertheless, does not

mean independence. The submission of bishops to the authority

of the Pope was affirmed in a very clear manner by the 1917

Code of Canon Law (Canon 329,§1):

Bishops

are the successors of the Apostles and through divine

institution are at the head of the local church, which

they govern with ordinary power under the authority of

the Roman Pontiff.12

In

the 1983 Code of Canon Law, as a consequence of the

democratic applications that Vatican II wished to exercise

in the Church, the principle of submission to the pope,

even if present, is stated in an ambiguous manner (e.g.,

in Canon 375,§1). Yet, while maintaining a millenary practice

(from Gregory VII on), even the 1983 Code of Canon Law

affirms that it is forbidden to consecrate a bishop

without episcopal mandate, that is, without the previous

authorization of the pope. And in fact the text of Prof.

Kaschewski continues thus:

2.

It is licit for no one to consecrate a bishop without

Pontifical mandate (1983 Code of Canon Law, Canon

1013). He who acts contrary to this canon incurs excommunication

latae sententiae reserved to the Apostolic See

(1983 Code of Canon Law, Canon 1382). One incurs

latae sententiae excommunication ipso facto

[by the fact itself], that is, at the very moment the

offense is committed, and it is not necessary that the

penalty be inflicted through a decree. For the illicit

consecration of a bishop the [1917 Code of Canon Law]

threatened only suspension [See 1917 Code of Canon

Law, Canon 2370; "They are suspended by the law

itself until the Apostolic See shall have dispensed them."

- Ed.]. Only with the decree of the Holy Office

(August 9, 1951), in consequence of the tragic turn of

events of the Church in the Chinese Communist Republic

[where bishops of the Chinese "Patriotic Church"

were being appointed by the governing communists - Ed.],

was the penalty of ipso facto excommunication introduced,

reserved to the Holy See specialissimo modo [in

a most special manner-Ed.]13

The

1983 Code of Canon Law does not give the definition

of excommunication, which must be taken from the 1917

Code of Canon Law (see Canon 2257ƒƒ.). It consists in

the (external) "exclusion" from the "communion

of the faithful." It belongs to that class of penalties

called censures which are: excommunication, interdict,

and suspension (1917 Code of Canon Law, Canon 2255,§1).

Censures are "medicinal" penalties because they

are meant to serve as a medicine for the one being disobedient

so that he may be convinced of his error and make amends.

At the moment in which the offender or "contumacious

one" recedes from his disobedience, the penalty ought

to be remitted for him.14Medicinal

penalties are distinguished from those called "vindictive"

[a.k.a. "expiatory" in the 1983 Code

of Canon Law - Ed.] which have instead as their essential

purpose not the correction of the offender, but the restoration

of the violated juridical order.15

The

effects of excommunication are grave because it involves

the prohibition of administering and receiving the sacraments.

Yet, it is an administrative type of sanction that can be

removed by the same authority that has inflicted it. Moreover,….

...the

communion from which one is excluded is not that internal

[communion], inhering in the soul and embracing the goods

of the theological life, as grace and the virtues of faith,

hope and charity , by nature invisible, but those external

visible goods, entrusted to the Church and ordained to

produce the internal spiritual goods or the other external

goods that are inseparably connected to the internal goods

(e.g., sacraments, sacrifice, ecclesiastical power,

etc.). Radical or ontological communion, which

makes us members [by means of baptism - Ed.] of

the Mystical Body of Christ is not called into question

by excommunication. 16

B.

Unjust Excommunication

Rev.

Fr. Gerald E. Murray

A species

of excommunication used to exist and still does exist among

theJews17

and St. John tells us that those Jewish leaders, who were

favorable to Jesus, did not dare to declare that He was

the promised Messias, for fear of being expelled from the

synagogue, that is, of being formally excluded from the

community of believers by decree of the proper authority.18

The

possibility exists therefore that excommunication may be

inflicted unjustly. The "excommunications" which

the unbelieving Pharisees and persecutors were threatening

or preparing to inflict upon the disciples of Our Lord,

are an example of unjust excommunication:

They

will put you out of the synagogues: yea, the hour cometh,

that whosoever killeth you, will think that he doth a

service to God. And these things they will do to you;

because they have not known the Father, nor me (Jn. 16:2,3).

Another

well-known example is the excommunication inflicted by Pope

Alexander VI on Savanarola.19

C.

Excommunication Latae Sententiae and Ferendae

Sententiae

There

are two types of excommunication: I) latae sententiae

is that excommunication where a sentence has been passed;

and 2) ferendae sententiae, an excommunication where

a sentence needs to be passed. These classifications give

the two most general categories of the penal law of the

Church, which find application even in the case of excommunication.

A canonical penalty is called latae sententiae when

"one incurs it by the very fact of having committed

a crime."20

This means that the penalty inheres, so to speak, in the

criminal deed, without having to wait for a judge or a superior

to inflict it by means of a sentence or a decree. On account

of this it is said that excommunication latae sententiae

is applied automatically. The application of the penalty

therefore has only declarative value, because the decree

or the sentence which contains it is limited to declaring

the existence of it. This is so much the case that the juridical

effects of the latae sententiae penalty are produced

"from the moment in which the criminal deed was completed"

(1917 Code of Canon Law; Canon 2232,§2) and not from

the moment of the sentence or declaration.

The

excommunication ferendae sententiae" is, on

the contrary, that which "must be inflicted by the

judge or by the superior."21

"This occurs as a rule after a trial. In this case,

the sentence or the decree are constitutive of the

penalty: they are not limited to declaring the existence

of a penalty that already inheres in a certain behavior,

but they cause it to come into being, they constitute the

term of the trial, which could, in fact, also be concluded

with an absolution. Therefore, the juridical effects of

the ferendae sententiae" penalty are produced

"from the moment of the sentence or decree," and

not from the moment in which the deed was committed. No

retroactivity exists here. In contrast to the situation

in the latae sententiae penalty, in the former case

of the ferendae sententiae penalty there cannot be

a penalty without a trial and consequent sentence or decree.

The difference is not small. The difference is so great

that the 1917 Code of Canon Law specifies that "the

penalty must always be understood ferendae sententiae,'

unless it is explicitly affirmed that it must be understood

as latae sententiae.22

D.

Imputability and Latae Sententiae Penalties

Every

modern penal law takes into consideration the subjective

element of the offense. In order that someone may be

able to be considered punishable, it is not enough that

he has committed the criminal act, but it is necessary that

he be imputable, that is to say that the breaking

of the law can be ascribed to him as an action of a subject

capable of understanding and willpower. In other words,

that the subject acted with a will freely directed to a

determined end. In order that there be full imputability,

it is necessary that the subject has acted with the intention

of offending [animus laedendi] or, as the Roman jurists

used to say, "with an evil intent." In fact Canon

1321,§2 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law says: "A

person who has deliberately violated the law or precept

is bound by the penalty prescribed in that law or precept…..

A weakened

form of imputability is that which considers not the malice,

but the fault, understood as the disposition of the subject

who does not show the animus laedendi, but a simple

"omission of due diligence." The distinction is

clear from the second sentence of Canon 1321,§2 of the 1983

Code of Canon Law, the first part of which we quoted

above: "...If, however, the violation was due to the

omission of due diligence, the person is not punished unless

the law or precept provides otherwise." In the case

of a culpable violation of the norm, the punishability can

be lessened.23

In

the law of the Church the subjective element has always

enjoyed a particular importance. This is derived from the

very character of the religious and moral conception that

the Church has practiced, defended, and developed through

its own juridical system.

In

order that the subject be punishable he must be imputable.

The 1983 Code of Canon Law states:

No

one can be punished for the commission of an external

violation of a law or precept unless it is gravely imputable

by reason of malice or of culpability (Canon 1321, §1).24

The

full imputability of the penalty is valid, therefore, for

whoever has deliberately violated the law with full

consciousness and intention. For such a motive, the 1983

Code of Canon Law demands that, in the case of latae

sententiae penalties which, as we have defined them,

are applied without a judgment, malice and full imputability

are always presumed.

The

condition of malice is required by Canon 1318 of the 1983

Code of Canon Law, which says:

A

legislator is not to threaten latae sententiae penalties,

except perhaps for some outstanding and malicious offenses

which may be more grave by reason of scandal or such that

they cannot be effectively punished by ferendae sententiae

penalties. He is not, however, to constitute censures,

especially excommunication, except with the greatest moderation,

and only for the more grave offenses.25

The

invitation of the Code to prudence and to caution

in a matter so delicate is substantiated in the specification

of three conditions necessary for the imposition of latae

sententiae penalties: 1) there must clearly

be malice on the part of its author; 2)

the offense must provoke grave scandal among the faithful;

3) the offense must not be punishable

through ferendae sententiae penalties.26

For

the purposes of our discussion, it is of interest that the

Code of Canon Law desired to place the accent on

the presence of malice as a necessary requisite for the

imposition of a latae sententiae penalty. But malice

can be demonstrated only if the subject is fully imputable,

since only to a fully imputable subject can the moral fault

of having deliberately wished to violate the law be attributed.

Therefore, if full imputability is lacking, the latae

sententiae penalty of excommunication cannot be legally

applied.

The

requirement of full imputability of the offender naturally

comes into play in every malicious crime. This is a general

principle of every modern penal system. All the more is

it valid for latae sententiae penalties, given their

exceptional character. And, in fact, Canon 1324,§1 [1983

Code of Canon Law], in ascribing ten circumstances attenuating

imputability, delineates in §3 of the same canon that in

all ten cases "...the offender is not bound by a latae

sententiae penalty ."27

E. Attenuating

Circumstances and Exemptions

Attenuating

circumstances do not eliminate imputabulity, but they do

reduce it. They prevent the imputability from be characterized

as "full." As a consequence of this, a mitigation

is had of the penalty already established or the substitution

of it by other sanctions, for example penances. Penances

are not technically penalties by definition, but replace

or increase them [1983 Code of Canon Law; Canon 1312,§3).

Canon 1324 states in §1:

The

perpetrator of a violation is not exempted from the penalty,

but the penalty prescribed in the law or precept must be

diminished, or a penance substituted in its place, if the

offence was committed by: 1° one who had only an imperfect

use of reason; ……

The

list of nine other attenuating circumstances follows the

first listed in the above quote.28

Among these nine other attenuating circumstances two are

of interest to us: Numbers 5 and 8. Number 5 considers the

case of one who was "compelled by grave fear, even

if only relative, or by reason of necessity or grave inconvenience,

if the act is intrinsically evil or tends to be harmful

to souls."29

The meaning of this part of Canon 1324 means that whoever

has completed an action "intrinsically evil or tends

to be harmful to souls," not deliberately, but only

on account of having been forced or from grave fear, necessity,

or grave inconvenience, is entitled to have take these circumstances,

which attenuate his imputability, taken into consideration.

This requires that the penalty not be imposed in its fullness

and/or it be substituted by another type of sanction, as

for example, a penance.

But

why doesn't the attenuating circumstances of Number 5 of

Canon 1324 eliminate all imputability? - Because

the action to which they have felt forced to perform was

itself "intrinsically evil" or tending to be "harmful

for souls." Given this nature of the action, it necessary

that a form of sanction be maintained in view of the common

good. Among the penalties which cannot be maintained.

however, is excommunication.

In

Number 8 of Canon 1324 on attenuating circumstances, there

is considered, on the other hand, the case of one "who

erroneously, but culpably, thought that some one of the

circumstances existed which are mentioned in Canon 1323,

Numbers 4 or 5."30

It reads:

No

one is liable to a penalty who, when violating a law or

precept acted only under compulsion of grave fear, even

if only relative, or by reason of necessity or grave inconvenience,

unless, however, the act is intrinsically evil or tends

to be harmful to souls; [or] acted, within the limits

of due moderation, in lawful self-defense or defense of

another against an unjust aggressor.

Besides

these two circumstances, Canon 1323 of the 1983 Code

of Canon Law gives five other circumstances that exempt

the agent from all imputability, rendering the application

of the penalty impossible. The exemptions

mentioned are those according to which the law has been

violated through grave fear even if relative, necessity,

and grave inconvenience when the act performed is not intrinsically

evil or does not tend to be harmful to souls or has been

performed through legitimate defense.31

Therefore, for that which regards the state of necessity

[the category which is important for us to analyze - Ed.],

when a norm has been violated with an act intrinsically

evil or harmful for the salvation of souls, there is had

a circumstance only attenuating, sufficient however for

excluding the application of excommunication which ought

to be substituted for by another penalty or by a penance.

On the other hand, if the norm was violated with an act

neither intrinsically evil nor harmful for souls, then imputability

absolutely does not exist and neither can a penalty nor

another form of sanction be inflicted. If the subject erroneously

thought himself to be within the conditions

given in Numbers 4 and 5 of Canon 1323 [1983 Code of

Canon Law], namely of being forced to act in a state

of necessity [or through grave fear, grave inconvenience,

or legitimate defense - Ed] without his action constituting

something wicked in itself or harmful for the salvation

of souls, then he has a claim on the attenuating circumstances.

This means that even if the action warrants excommunication,

this cannot be declared because it must be

substituted by another penalty or by a penance. When the

error of judgment takes place without fault on the

part of the acting subject, then, rather than laying claim

to an attenuating circumstance, the subject has claim to

an exempting circumstance:

No

one is liable to a penalty who, when violating a law or

precept thought, through no personal fault, that some

one of the circumstances existed which are mentioned in

Numbers 4 or 5 [1983 Code of Canon Law; Canon 1323,

n.7].

Causidicus

(edited by Rev. Fr. Kenneth Novak)

[This

article continues in a second episode the canonical

aspect of the double study of the 1988 Episcopal Consecration

of Archbishop Lefebvre. The SISINONO issues of

July

and September

(1999) dealt with the theological aspect. The third

installment of the canonical study will appear in the

March 2000 issue of SISINONO. - Ed.]

1.

See "Gaps in the New Code?" an interview with

Fr. Gerald E. Murray followed by a detailed enough exposition

of his thesis, "Schism, Excommunication, and The Society

of St. Pius X" edited by Steven Terenzio on pp.50-55

respectively in The Latin Mass (Fall, 1995). For

another interview with Fr. Murray see 30 Days, n.4,

April, 1995, pp.17,18.

2.

Mise au point du Conseil Pontifical pour I'interpretation

des textes legislatifs in La documentation catholique,

79 (1997), 2163, of July 6, 1997, pp.621-623. The retraction

of Fr. Murray is found in The Latin Mass (Summer,

1996; pp.54,55). The Mise au point has been translated

into Italian in Il regno-Documenti, n.17 ,1977, pp.528,529.

The Letter to Friends and Benefactors, #53 of the

Society of Saint Pius X (Sept. 23, 1997) points out that

the Mise au point and a simultaneous document from

the Congregation of the Faith on the canonical situation

of the "lefebvrists" presented by Msgr. Brunner

are in reality anonymous documents without date nor protocol

number. For these reasons an obligatory value cannot be

granted to them. These documents are evidence of the persistent

hostility of the French and Swiss episcopates towards the

Society of Saint Pius X.

3.

This has been emphasized by Fr. Michel Beaumont in the article

"L'abbé Gerald Murray se fait taper sur les doits,"

which appeared in an issue of Fideliter (1997), pp.41-46,

strongly critical of the "retraction" of the American

scholar: "But this is the explicit approbation given

by the highest academic instance, the Pontifical Gregorian

University of Rome, which confers on this work an exceptional

value." This value is not able to be lessened in light

of its retraction otherwise we would have to say that the

professors of the Gregorian must retract their scientific

approval! (Fr. Albert O.P. "La these de l'abbe Murray"

in Le sel de la terre, n.24, Spring 1998, pp.50-67).

4.

See Is Tradition Excommunicated?, "The Episcopal

Consecrations: A Canonical Study," pp.l03-110. [Available

from Angelus Press. Price: $7.95].

5.

Is Tradition Excommunicated? cit., p.110.

6.

SISlNONO, Ne schismatici ne excomunicati; Albano

1997, p.28ƒƒ.

7.

SISINONO, October 1988 (XIV, 17,p.4).

8.

Op. cit, p.1.

9.

Le sel de la terre (1993) 4, pp.27-45; 5, pp.44-87;

7, pp.25-57; (1994) 8, pp.28-44. The original is in German:

"Bischofsweihen durch Erzbischof Lefebvre. Theologische

Untersuchung der Rechtmassigkeit" ["The Episcopal

Consecrations of Archbishop Lefebvre: A Theological Examination

of their Legitimacy"], Zaitzkofen, 1992.

10.

The book is interesting for its numerous comparisons between

the 1917 Code of Canon Law and the 1983 Code of

Canon Law. The 1917 Code of Canon Law is also

called the Pian-Benedictine Code because it was compiled

through the initiative of Pope Pius X and promulgated under

Pope Benedict XI (Sept. 15, 1917). The 1917 Code of Canon

law is known for its conceptual and systematic vision.

11.

Kaschewski. French translation in La tradition excommuniee,

cit., pp.51-57, p.51.

12.

"Episcopi sunt Apostolorum successores atque ex

divina institutione peculiaribus ecclesiis praeficiuntur

quas cum potestate ordinaria regunt sub auctoritate Romani

Pontificis."

13.

Kascewski, op. cit., p.4; French translation cit.,

pp.51-52

14.

See Commento al Codice di Diritto Canonico [a.k.a.,

Commento] edited by Msgr .Pio Vito Pinto, Urbaniana

University Press, Rome, 1985, pp.771, 772; see Del Guidice

Istituzioni di diritto canonico, 12th revised ed.

in collaboration with G. Catalano, Milan, 1970, p.488ƒƒ.

15.

See Commento cit. p.777; Del Giudice op. cit,

p.488 ƒƒ.

16.

Commento, p.772.

17.

See "Das Mosaïsche-Rabbinische Strafgesetze und Strafrechtliche

Gerichts Verfahren ["The Mosaic-Rabbinical Penal Law

and Penal Procedure"] edited by Head Rabbi Hirsch B.

Fassel, Gross-Kanischa, 1870, reprinted anast., Scientia,

Aalen, 1981, sec.lI, §13, p.12.

18.

Jn. 12:42-43. An Old Testament reference is found in Prov.

22:10: "Cast out the scoffer and contention shall go

out with him, and quarrels and reproaches shall cease."

19.

See the biography of R. Ridolfi, Vita di S. Girolamo

Savonarola, Firenze, 1974, 5th ed., pp.283ƒƒ

20.

Canon 2217, §1, 2° [1917 Code of Canon Law]:

'Poena dicitur...latae sententiae, si poena determinata

ita sit addita legi vel praecepto ut incurratur ipso facto

commissi delicti; ferendae sententiae, si a iudice vel superiore

infligi debeat." The penalties latae sententiae

and ferendae sententiae are considered also in the

1983 Code of Canon Law, but for their definition

it is necessary to go back to the former 1917 Code of

Canon Law. The "fixed" penalty is that established

especially by a norm addressed to all [law] or individually

specified persons [precept]: "Poena dicitur: Determinata

si in ipsa lege ver praecepto taxative statuta sit'

[Canon 2217, cit.l, 1°].

21.

Canon2217,§2, 2°, 1917 Code of Canon Law, cit.

22

Canon 2217 cit., §2, "Poena intelligitur semper ‘ferendae

sententiae,' nisi expresse dicatgur eam esse latae sententiae

vel ipso iure contrahi, vel nisi alia similia verba adhibeantur."

The concept is reaffirmed in the 1983 Code of Canon Law,

which in Canon 1314 reassumes the exposition of the 1917

Code: "Poena plerumque est 'ferendae sententiae’, ita

ut reum non teneat, nisi postquam irrogate sit; est autem

'latae sententiae, ' ita us in eam incurratur ipso facto

commissi delicti, si lex vel praeceptum id expresse statuat."

[See p.753 of the Commento cit.: "The penalty is generally

ferendae sententiae, such that it does not oblige the guilty

one if it has not afterwards been inflicted; but it is latae

sententiae such that it is incurred through the very fact

of the offense having been committed, if the law or the

precept expressly establish it."] On the declarative

and constitutive significance of the act of the condemned,

see Commento cit., p.489.

23.

The whole of Canon 1321 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law

reads: "1) No one can be punished for the commission

of an external violation of a law or precept unless it is

gravely imputable by reason of malice or of culpability.

2) A person who deliberately violated a law or precept

is bound by the penalty prescribed in that law or precept.

If, however, the violation was due to the omission of due

diligence, the person is not punished unless the law or

precept provides otherwise. 3) Where there has been

an external violation, imputability is presumed, unless

it appears otherwise." [On this canon and its relation

to the 1917 Code see Commento, cit., pp.758-759.

The definitions present in the 1917 Code are clearer: cf.

1917 Code of Canon Law, Canons 2199; 2200.]

24.

The canon has already been reported in its entirety in footnote

§13.

25.

This canon re-echoes Canon 2241, §1, of the 1917 Code

of Canon Law: "Censures, especially latae sententiae,

most of all excommunication, are not to be inflicted, except

moderately and with great circumspection."

26.

Examine Commento, cit., on p.756.

27.

Commento states: §3 [of Canon 1324 of the 1983

Code) articulates a general principle that every diminution

of imputability frees from latae sententiae penalties

otherwise demanding full imputability [cf. Canon

2218,§2 of the 1917 Code.] When it is a question

of latae sententiae penalties, the judgment of whether

one of the causes (cited in Canon 1324) exists is the concern

of the delinquent himself. This is different from what happens

in ferendae sententiae penalties in which there is

a judge to establish whether or not the cause exists [Commento,

cit., pp.765-766]. If §3 of Canon 1324 states a general

principle, this ought to be valid then for all cases in

which a latae sententiae penalty is foreseen, even

for apostasy, heresy, and schism [1983 Code, Canon

1364,§1). Lacking full imputability, they would never be

able to be punished by incurring a latae sententiae

excommunication.

28.

“Violationis auctor non eximitur a poena, sed poena lege

vel praecepto statuta temperari debet vel in eius locum

paenitentia adhiberi, si delictum patratum sit: lº

ab eo, qui rationis usum imperfectum tantum habuerit."

See also Commento, cit., pp.763 ƒƒ.

29.

See Commento, cit., p.762: "The general principle

of Canon 125,§2 [1983 Code under "Title VlI:Juridical

Acts" - Ed.] decrees that an act performed as a result

of fear which is grave and unjustly inflicted is valid unless

the law provides otherwise. However, in a penal matter whether

absolute or relative, having taken into account the subject

who places the threat and whoever undergoes it, it frees

from every penalty."

30.

“...ab eo, qui per errorem, ex sua tamen culpa, putavit

aliquam adesse ex circumstantiis, de quibus in can. 1323,

nn.4 or 5."

31.

"...metu gravi, quamvis relative tantum, coactus

egit, aut ex necessitate vel gravi incommodo, nisi tamen

actus sit intrinsece malus aut vergat in animarum damnum.

"

Courtesy of the Angelus

Press, Kansas City, MO 64109

translated from the Italian

Fr. Du Chalard

Via Madonna degli Angeli, 14

Italia 00049 Velletri (Roma)

|

![]()

![]()